Hydraulic fracturing—better known as fracking—and other technological advances, such as horizontal drilling, have resulted in the rapid expansion of "unconventional" oil and gas extraction.

Communities across the country now face difficult decisions on fracking. Promises of economic growth have led many communities to embrace unconventional oil and gas development, but questions about environmental and health risks, and about the duration and distribution of economic benefits, are causing deep concern.

These decisions become especially challenging when the public lacks reliable information about the impacts of fracking. Inadequate governance, interference in the science, and a noisy public dialogue all create challenges for citizens who want to be informed participants in fracking discussions.

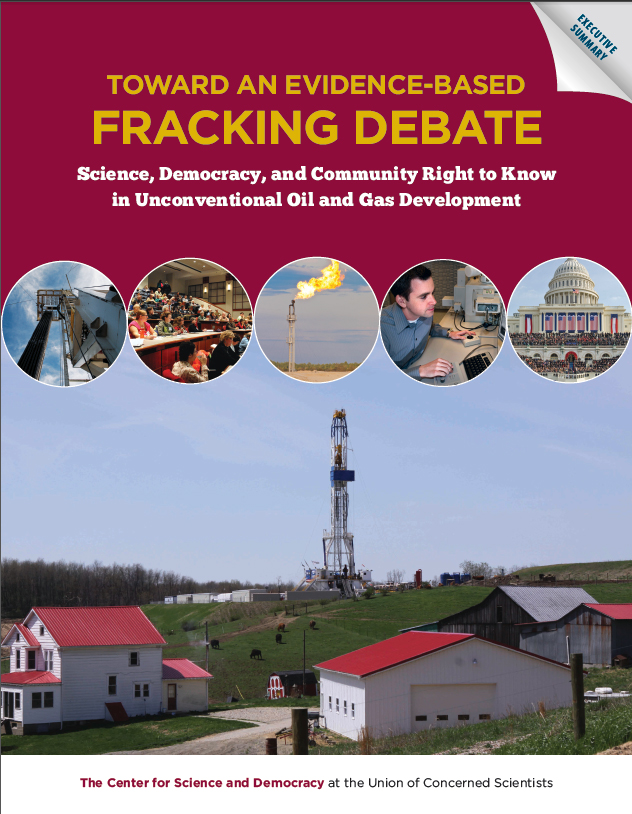

The 2013 Center for Science and Democracy report, "Toward an Evidence-Based Fracking Debate: Science, Democracy, and Community Right to Know in Unconventional Oil and Gas Development," examines the current state of the science on fracking risk as well as the barriers that prevent citizens from learning what they need to know to help their communities make evidence-based decisions.

Along with this report, we have developed a toolkit for active citizens and policy makers faced with decisions about unconventional oil and gas development in their communities. By providing practical advice and resources, the toolkit helps citizens identify critical questions to ask, and obtain the scientific information they need to weigh the prospects and risks in order to make the best decisions for their community.

To read or print the toolkit, go to www.ucsusa.org/HFtoolkit.

A lack of transparency

Communities seeking reliable information about fracking often run into barriers:

- Most companies do not disclose complete information about the chemicals used in fracking, claiming that this data is proprietary and its disclosure could hurt their business.

- Companies have restricted access for scientists conducting research that is crucial for understanding the impacts of fracking.

- Since lawsuits brought by citizens affected by fracking usually end in non-disclosure agreements, data used as evidence in these cases is unavailable to the public or to scientists.

To remove such obstacles, companies should be required to collect and publicly disclose three kinds of data:

- Baseline studies of air, water, and soil quality before drilling begins;

- Monitoring studies during and after extraction activities;

- The chemical composition, volume, and concentration of the chemicals used in their operations.

Such concrete data will enable scientists to quantify risk, empower citizens with reliable information, and help hold polluters accountable.

Misinformation and interference in the science

With large profits at stake, it is perhaps not surprising that government and academic research on fracking's environmental and socioeconomic effects has been subject to interference from political and corporate forces.

The EPA, on multiple recent occasions, has begun to act against industry actors whose fracking activities were found to have caused environmental damage—only to back off in the face of pressure from the companies themselves or sympathetic politicians.

Academic study of fracking, too, has been vulnerable to corporate interference. The University of Texas published a study in 2012 that was strongly criticized after the lead author was revealed to have ties to an energy industry firm. And SUNY Buffalo was forced to close its Shale Resources and Society Institute in response to similar criticism about the relationship of some of its professors to the natural gas industry.

Legal limitations and loopholes

One might think that laws like the Clean Water Act, and regulatory agencies like the EPA, would provide adequate protection against possible fracking risks. However, it turns out that federal laws and regulations are full of loopholes and shortcomings. (Perhaps not coincidentally, the industry spent $750 million on lobbying and political contributions between 2001 and 2011.)

- Most fracking operations are exempt from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act and parts of the Clean Water Act thanks to a provision in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 commonly known as the "Halliburton loophole" (because former Halliburton CEO—and then Vice President—Richard Cheney chaired the task force that recommended the exemptions).

- The Bureau of Land Management in May 2013 released revised regulations to address such exemptions on public and tribal lands, but the new regulations again have troubling loopholes regarding chemical disclosure.

- State and local governments have attempted to fill the regulatory gap, but the result is a patchwork of old and new rules varying from state to state, with important protections often absent.

Empowering the public

Community members looking for answers on fracking must navigate a noisy and often misleading information landscape. To maximize the chance of finding reliable information, citizens should:

Seek out objective sources. Government sources usually provide objective information. Government websites can be hard to find, however; try using the phrase "hydraulic fracturing" rather than "fracking" in a web search. Another potential source of objective information is the insurance industry, which relies on factual information and accurate risk assessment.

Carefully navigate media sources. The public should look for stories that neither stoke nor dismiss concerns, but accurately represent the work scientists are doing and explain, without exaggerating, the complex relationship between uncertainty and risk.

Watch out for misinformation. Citizens must carefully navigate through messages from fracking stakeholders. Misinformation rarely takes the form of outright falsehoods; instead it may appear as half-truths, exaggerations, omissions and misrepresentations. Stakeholders on both sides may skip over nuances, uncertainties, limitations and caveats in scientific studies in their eagerness to use the research as evidence supporting their views.

Community right to know

The public has a right to reliable information:

- about the likely impacts (negative and positive) of unconventional oil and gas development on their community;

- about the uncertainties and limitations of our scientific knowledge;

- about what is covered by regulations—as well as what isn't, but should be.

Ultimately, citizens need to be empowered with the information they need to make informed decisions about unconventional oil and gas development in their communities.