Children need healthy food. This should go without saying, but the current U.S. food system makes it hard to ensure that kids get the kinds of foods they need to grow into healthy adults. The average U.S. child eats only one-third of the fruits and vegetables recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

This problem is especially acute for children from lower-income and racial and ethnic minority families. These children often lack adequate access to fresh, healthy food, while unhealthy processed foods—made artificially cheap in part by federal subsidies—are readily available. Coupled with environmental factors, this leads to a predictable result: high obesity rates.

The costs of childhood obesity

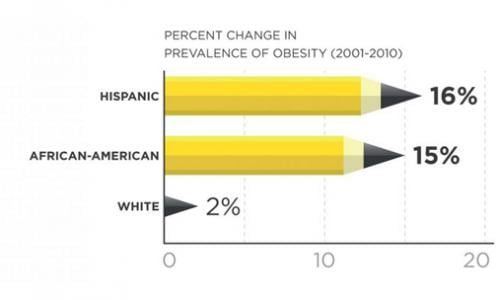

Obesity rates among children nearly tripled between 1970 and 2000; today approximately 16% of US youth are classified as obese. Obesity has disproportionately affected minority children, especially in recent years: since 2000, the rise in obesity rates has leveled off for white children, but it continues to climb for Black and Hispanic children.

Obese children are 10 times more likely than their peers to become obese adults—and adult obesity has serious health consequences, including increased risk of type II diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic diseases. These impacts not only mean shorter and less fulfilling lives for millions of people; they also carry a heavy price tag in health care costs.

Childhood obesity also plays a key role in a cycle that can trap low-income children: poor health and missed school days result in lower academic achievement, which leads to lower-paying jobs—and low incomes make it harder to maintain healthy lifestyles.

The role of school lunch

Healthy school lunches can be a key factor in breaking this cycle by improving kids’ diets. Children consume about half of their daily calories at school; for low-income children, school lunch may be their only real meal of the day. And the foods kids eat at school influence their lifelong eating habits.

For decades, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has administered school meal programs that provide funding to support free and reduced-price (FRP) meals for students who meet income eligibility criteria. Meals offered under the program must meet nutritional standards.

In recent decades, subsidized school meals had tilted toward processed foods high in fat, sugar, and sodium. In response to these trends, Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA) of 2010, which required the USDA to update its standards for school meals to align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Schools began implementing these new standards in 2012.

School lunch works—but it faces an uphill battle

The report shows that school lunch programs have a positive impact on the eating habits of students. Fifth grade FRP meal participants ate fruits and vegetables 22.2 times per week on average, versus 18.9 times for non-FRP participants. While both groups ate fewer fruits and vegetables in eighth grade, FRP meal participants continued to eat them more often than their non-FRP peers (19.2 vs. 17.6 times per week).

Unfortunately, the positive impact of school food programs is not strong enough to overcome other unhealthy influences on children’s diet. Our analysis found that FRP meal participants drank more sugary beverages and ate more fast food than their peers, and they were more likely to be obese—gaps that widened between 5th and 8th grade.

Stronger standards make a difference

Starting in 2012, schools began to implement the stronger nutrition standards mandated by HFFKA. While researchers are still in the early stages of evaluating the effectiveness of the updated standards, the evidence so far is promising. For example, a 2014 Harvard School of Health study found that vegetable consumption increased by 16.2 percent in the first year of implementation at four low-income schools. Other studies have shown that changes to the way healthy foods are presented and marketed in the cafeteria can have significant benefits.

Recommendations

Stronger school lunch policies have made a positive difference in children’s diets—and Congress needs to build on these gains by improving those policies further. The report has several specific recommendations for Congress as it renews the HHFKA in 2015:

- Protect gains made in 2010

- Increase the federal meal reimbursement rate

- Improve nutrition education

- Finance school cafeteria kitchen equipment

- Prioritize fruits and vegetables

- Increase funding for the Farm to School grant program

- Not allow politics to trump science