Climate change is producing hotter, drier conditions in the American West, which contribute to more large wildfires and longer wildfire seasons.

Climate change is producing hotter, drier conditions in the American West, which contribute to more large wildfires and longer wildfire seasons.

The risk to people and their homes is rising as a result, a growing danger made worse by the increasing number of homes and businesses being built in and near wildfire-prone areas. Past fire suppression and forest management practices have also led to a build-up of flammable fuel wood, which increases wildfire risks.

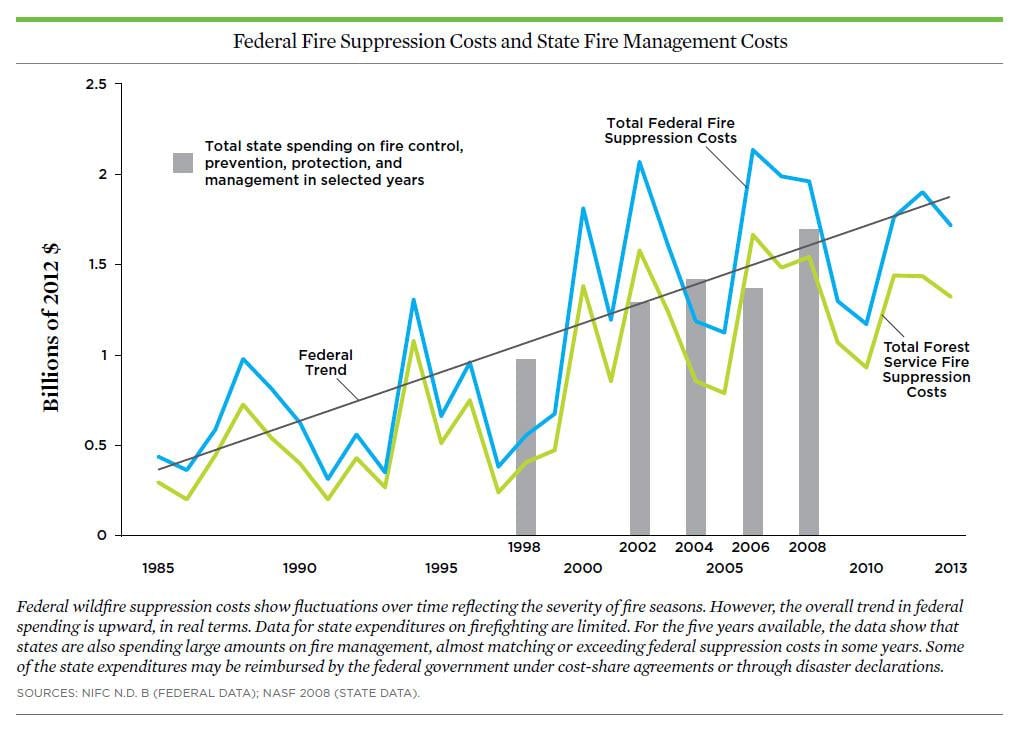

Costs are soaring in response. The expense of fighting wildfires and protecting life and property from harm is nearly four times greater than it was 30 years ago and has exceeded $1 billion every year since 2000 (in 2012 dollars).

Other costs, including the impact on public health, property, ecosystems, and livelihoods, are significant, often far exceeding firefighting costs.

Right now we are failing to effectively manage this mounting risk. We must make better use of our resources to more effectively manage wildfire risks and prepare for the growing consequences of climate change.

Learn more: State case studies (PDF)

Climate change is increasing wildfire risks

- Temperatures in the American West have gone up quickly. Since 1970, they have increased by about twice the global average.

- Snow melts earlier in the spring. Hotter, drier conditions last longer than they used to. The result is a longer wildfire season and conditions that are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.

- The western wildfire season has grown from five months on average in the 1970s to seven months today. The annual number of large wildfires has increased by more than 75 percent.

- This is a recent and dangerous alteration of the natural, long-standing, and necessary role of wildfires as part of the forest landscape.

- The threat of wildfires is projected to worsen over time as rising temperatures lead to more frequent, large, and severe wildfires and longer fire seasons.

- Since 1970, regional temperatures have increased by 1.9 degrees Fahrenheit. By mid-century, temperatures are expected to increase an additional 2.5 to 6.5 degrees Fahrenheit.

Development patterns are making it worse

In the last 50 years, there has been a significant expansion of development near wildland areas in the U.S., which often feature heightened wildfire risk. Much of this development comes from new homes.

- In 2000, the U.S. wildland-urban interface (WUI) contained more than 12.5 million housing units, a 52 percent expansion from 1970.

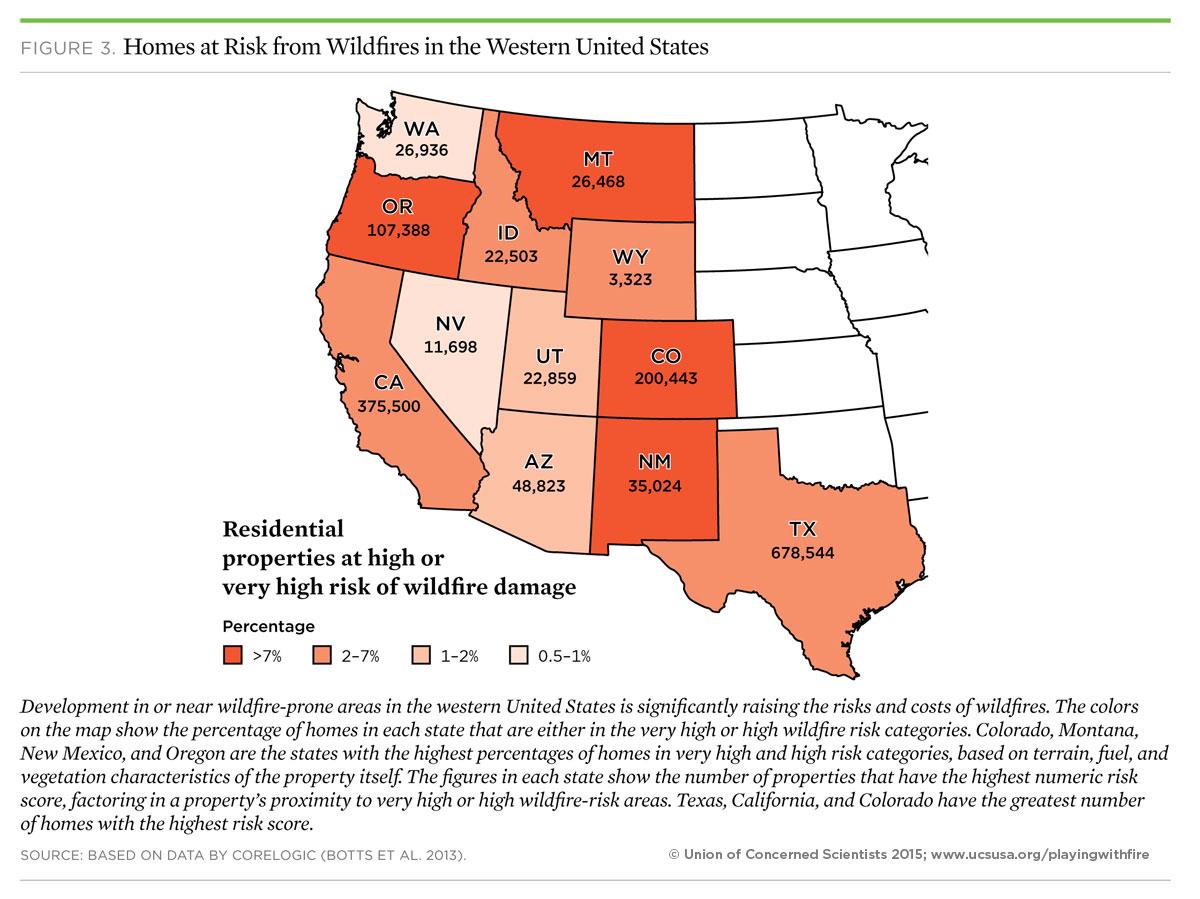

- More than 1.2 million homes — with a combined estimated value of more than $189 billion — across 13 western states are at high or very high risk of wildfires.

- Most of the highest-risk properties are in California, Colorado, and Texas, which together have nearly 80 percent of these properties in the western states.

The costs of wildfires are soaring

- The costs of putting out wildfires have increased dramatically in recent decades. Since 1985, fire suppression costs have increased nearly fourfold from $440 million to more than $1.7 billion in 2013 (2012 dollars).

- The share of the Forest Service budget devoted to fire management rose from 13 percent in 1991 to more than 40 percent in 2012.

- The long-term costs of wildfires continue long after they're put out. Damage to property, infrastructure, watersheds, and local economies are often an expensive legacy. Smoke from fires has significant health impacts. Flood risks increase in a post-fire landscape. Revenue from tourism and other area businesses often declines.

- The total wildfire costs can range anywhere from two to 30 times the direct suppression costs.

We are mismanaging the risk

- Some current federal, state, and local policies and commercial practices are worsening the impacts and costs of wildfires.

- Federal fire management is disproportionately skewed toward suppressing wildfire at the expense of efforts to proactively reduce wildfire risks and maintain healthy forests.

- State and local zoning priorities continue to allow development near forests, creating a misalignment with actions that can help reduce wildfire risks. In many cases, the full actual wildfire risks are not reflected in premiums for fire insurance.

- In the western U.S., where almost half of the land is federally owned, much of the funding for wildfire suppression comes from federal sources, ultimately the American taxpayer. In contrast, nearly 90 percent of the developed areas located in or near forests are privately-owned lands — and nearly two-thirds of them are at high risk of wildfire.

- We must do a better job of aligning limited federal and state firefighting budgets with state and local zoning decisions and private incentives to build in risky areas.

Solutions to help reduce wildfire risks and costs

- To better prepare for wildfires, protect people, and help maintain healthy forests, we should incorporate the latest science to improve wildfire mapping and prediction; invest in public awareness, fire-proofing, and fire safety measures; and ensure that forest and fire management practices reflect changes in climate.

- To reduce exposure to wildfire risk, development patterns and zoning policies should limit further building of homes in high-risk areas, insurance premiums should reflect actual wildfire risk, and homeowners and local communities should incentivize fire-proofing measures and assume more responsibility for mitigating wildfire risk.

- To effectively address the growing long-term wildfire risks caused by global warming, we must take steps today to reduce the heat-trapping emissions that are driving climate change.