It’s not exactly breaking news that people in the United States eat too much sugar. And a growing body of scientific evidence attests to the harm excess sugar consumption does to our health.

One promising strategy for breaking our national sugar addiction is to help young children learn healthy eating habits—with appropriately low levels of added sugar—while their tastes are still developing. Federal policies based on the scientific consensus about added sugar risk could provide crucial support for parents in this effort. But these policies are currently falling short in several important ways. And the food industry, which helped to engineer this policy shortfall, is exploiting it with marketing aimed squarely at kids—especially children of color.

The sugar deluge and how it harms kids

To get a sense of the magnitude of the problem, consider this: a 2010 study found that over 90 percent of children ages two through eight get more than half of their daily calories from added sugars. That's five times the 10 percent limit that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Department of Agriculture (USDA) have recommended.

These habits are formed early. A 2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study found that infants who drank sugar-sweetened beverages were more likely to be consuming these beverages more than once a day at age six. And these beverages are often so packed with sugar that a single serving will meet or exceed a child's recommended daily limit.

The impacts are devastating and costly. Higher levels of added sugar consumption mean increased risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic illnesses. And the risks are magnified in Black, Hispanic and Native American communities, as well as low-income households.

Big Food and its little targets

Two 2014 UCS reports, Sugar-coating Science and Added Sugar, Subtracted Science, documented the food industry's use of deceptive marketing, lobbying, and misinformation to increase sugar consumption and prevent effective policy responses.

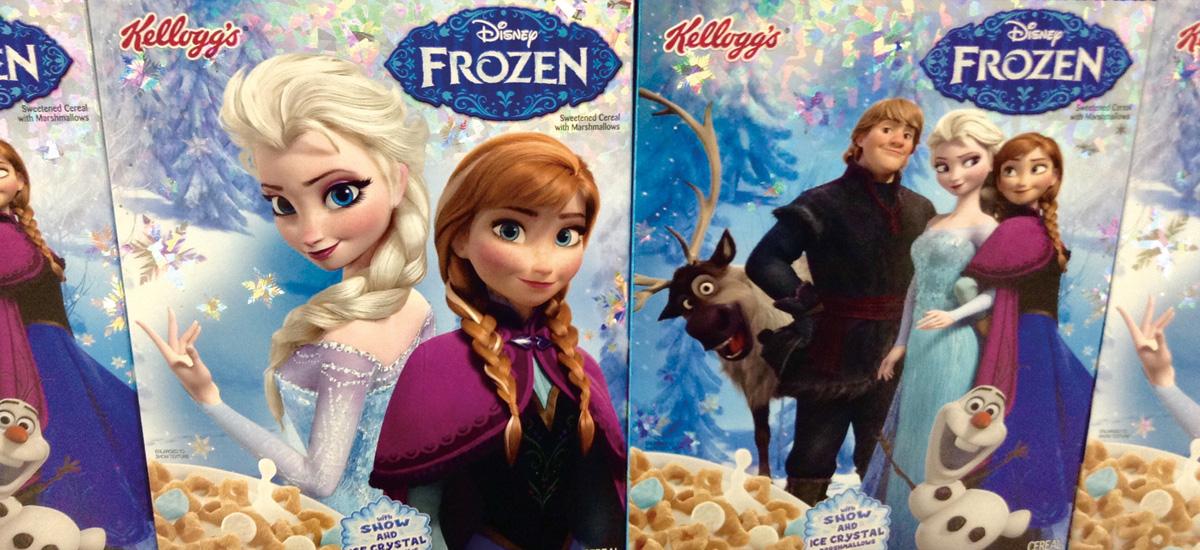

The food industry has a long history of marketing sugary foods to children, taking advantage of their biologically programmed preference for sweet tastes. According to a 2012 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) report, the food industry spends $1.8 billion each year on ads directed at children.

Multiple studies show that these marketing efforts are especially likely to reach children of color and low-income kids. This is no accident: food companies are not shy about acknowledging the importance of children of color to increasing their profits—even if this means knowingly exacerbating racial and economic health disparities in the United States.

If you thought the FTC was regulating such tactics, think again. After decades of intense pressure from the food and sugar industry, the FTC has given up its efforts to restrict advertising of sugary products to children. Instead, the industry has become essentially self-regulating.

Federal policy falls short

There are several federal policy levers that could help parents limit their kids' added sugar intake, including dietary guidelines, food labeling requirements, and nutritional standards used by supplemental food programs.

However, these programs and policies currently fall short of doing that job in several ways:

- The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, developed by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), have two major shortcomings. First, they address only the dietary needs of children two years old and older. Second, they apply the same recommended limit for added sugar intake—10 percent of daily calories—to all ages, even though many experts have recommended a lower percentage for young children.

- The FDA requires a separate Nutrition Facts label for infants and children under four years old. However, this rule only applies to foods explicitly aimed at under-four children. Four-year-olds are treated, for labeling purposes, like 30-year-olds, even though they are much more like three-year-olds in their eating habits. So parents who are trying to limit the added sugar consumption of their children ages four and over get limited help from the labeling rules.

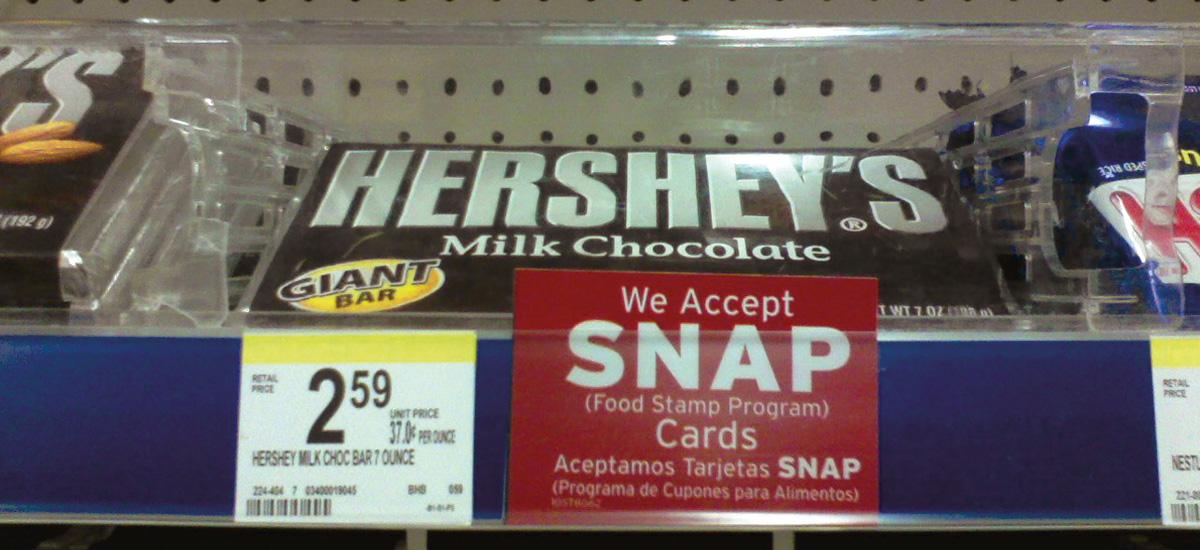

- The nutritional standards used by supplemental food programs such as WIC, SNAP, and CAFCP have not caught up to current dietary guidelines. A parent or preschool staff member who serves a child a cup of yogurt that meets WIC standards may not realize that the child has just eaten more than its entire daily recommended amount of added sugar.

Recommendations

Many stakeholder groups have a role to play in addressing the epidemic of excessive added sugar consumption in children’s diets. Listed below are summaries of some of the key recommendations presented in the report (for the full set of recommendations, download the report PDF):

HHS and USDA. Close the gap in nutrition advice for children from birth to two years of age by using the best available science in developing the 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans with inclusion of this age group; consider lowering daily added sugar limits for children birth through five; ensure transparency around conflicts of interest for members of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee.

FDA. Reduce the daily recommended limit for added sugars for four-year-olds to 25 grams from the current 50 grams; designate a disqualifying level for added sugars, above which food products may not contain health claims.

USDA. Implement a targeted education campaign for parents and child-care providers of infants and young children on reducing added-sugar consumption; revise WIC food packages to align with recommendations on added sugar in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine). Encourage the maintenance of a robust and transparent dietary guidelines process, and push for increased flexibility in WIC food packages.

Food and beverage manufacturers. Reduce the amounts of sugar added to foods and drinks intended for young children, and strictly follow federal guidelines as well as voluntary commitments to not market junk foods to young children under age six.