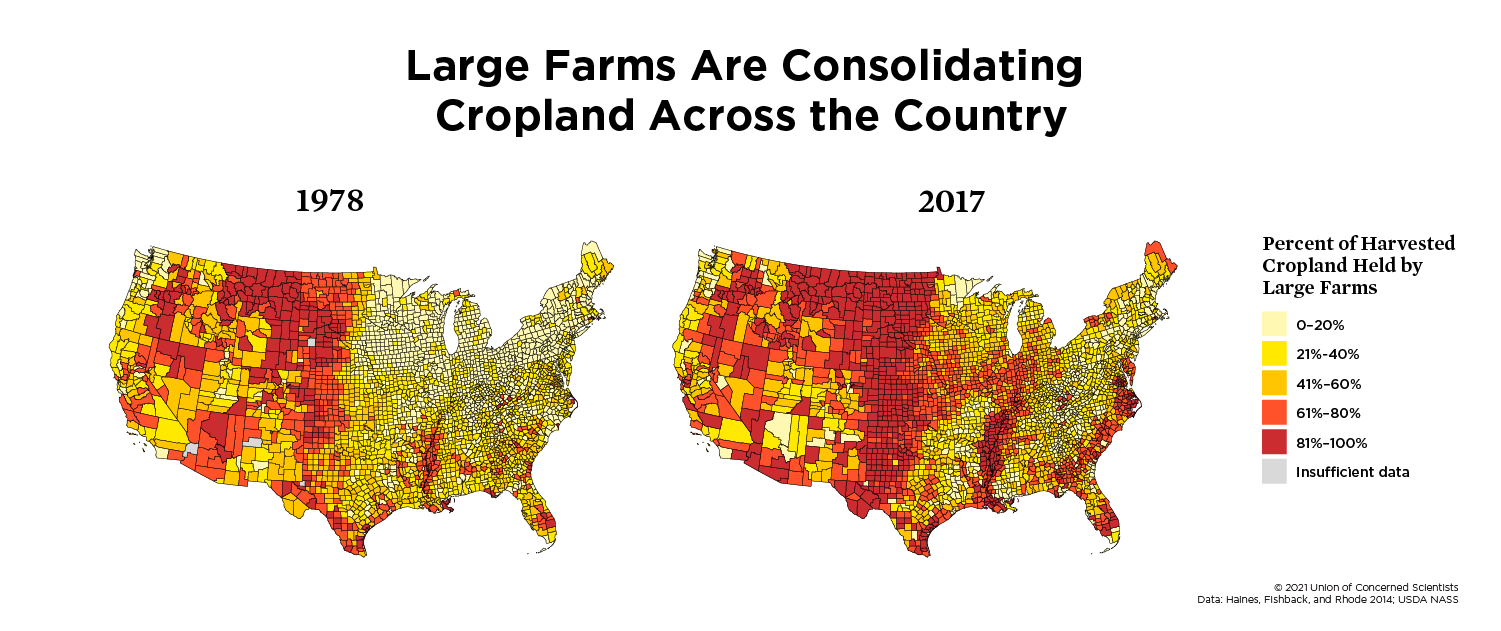

Over the past four decades, a lot has changed about US agriculture. One of the biggest changes has been the increasing predominance of very large farms, a trend known as farmland consolidation.

Consolidation has had troublesome consequences for many rural communities. It has come primarily at the expense of midsize farms, which have historically been the economic backbone of these communities. It has reduced opportunities for new farmers, who have become increasingly rare—and this has hit Black farmers, already fighting an uphill battle against multiple barriers imposed by structural racism, especially hard.

In a 2021 analysis, Losing Ground, we looked at US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Census of Agriculture data from the years 1978 through 2017 to connect the dots between farmland consolidation and steep declines in the share of new farmers and Black farmers in US agriculture.

The big get bigger

Consolidation happens when large farms acquire land that formerly belonged to smaller ones. Government policies that have consistently favored larger farms—along with the competitive advantage granted by economies of scale—made consolidation into a pervasive trend across the country for nearly a century. Over time, this has has meant a shrinking number of farm operations, as more land is taken up by a small number of larger and larger farms.

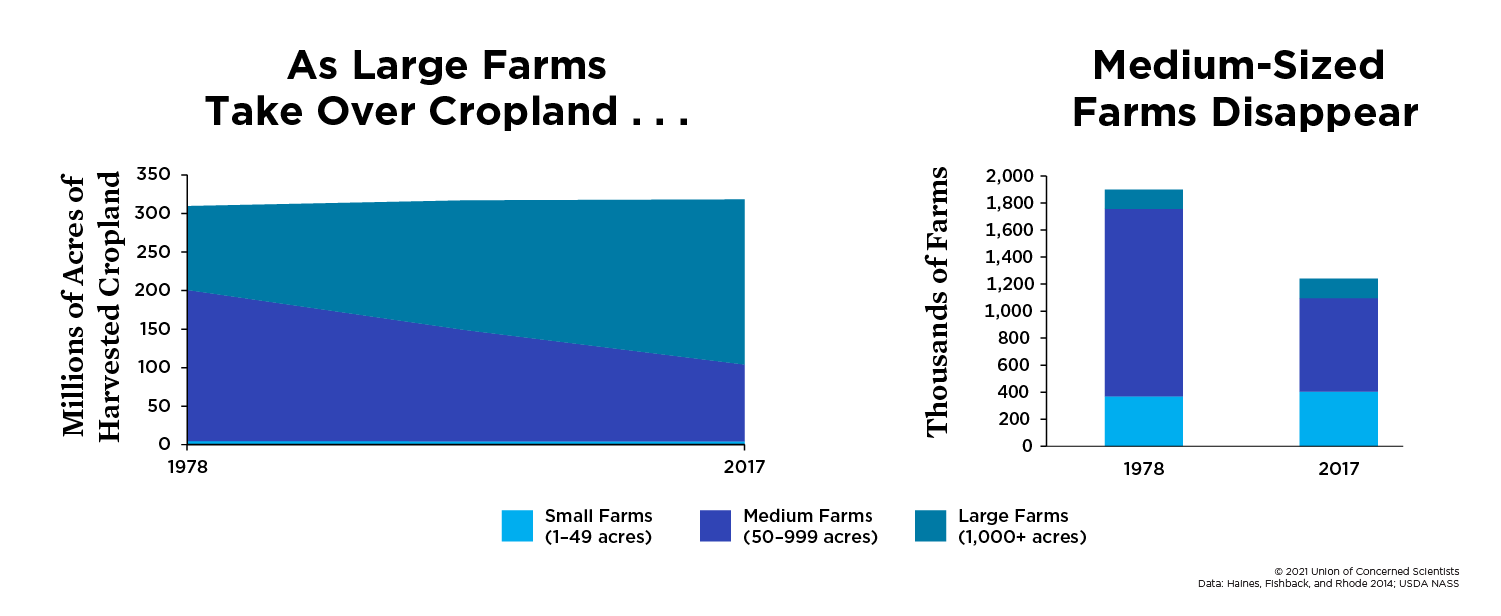

Over the 40-year period of our study, overall US farmland acreage declined 13 percent. But the amount of harvested cropland in large farms—those with more than 1000 acres—nearly doubled, growing by an area larger than the state of California. At the same time, midsize crop farms (50-1000 acres) shrank to just half of their former number and acreage. Though the number of small crop farms (less than 50 acres) increased, their total acreage decreased, indicating that their average size is shrinking.

As the study sums it up, “large crop farms are getting larger, small crop farms are getting smaller, and midsize crop farms are disappearing.”

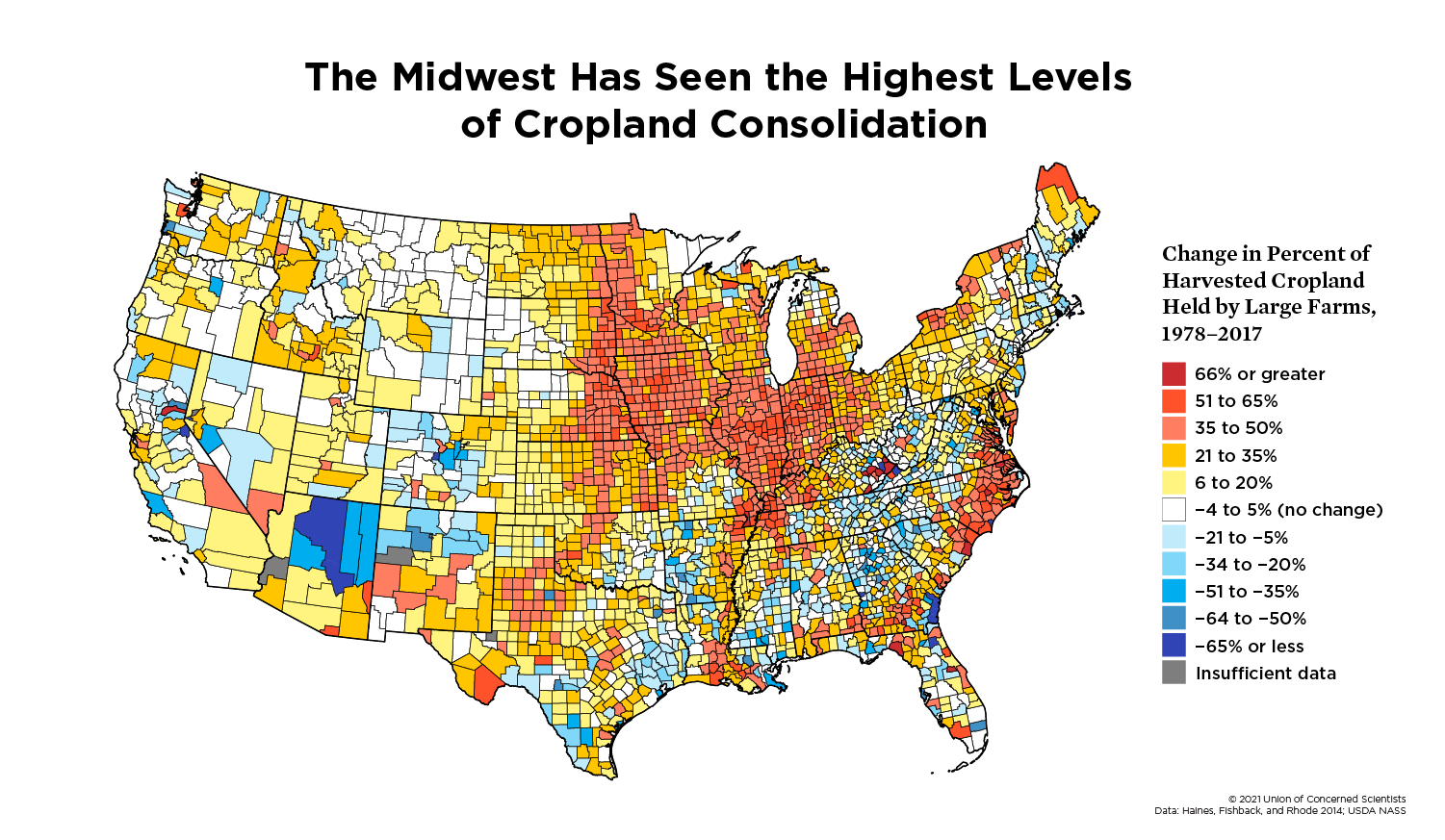

Nowhere are these trends more pronounced than in the Midwest, where harvested cropland in large farms more than quintupled.

Consolidation means exclusion

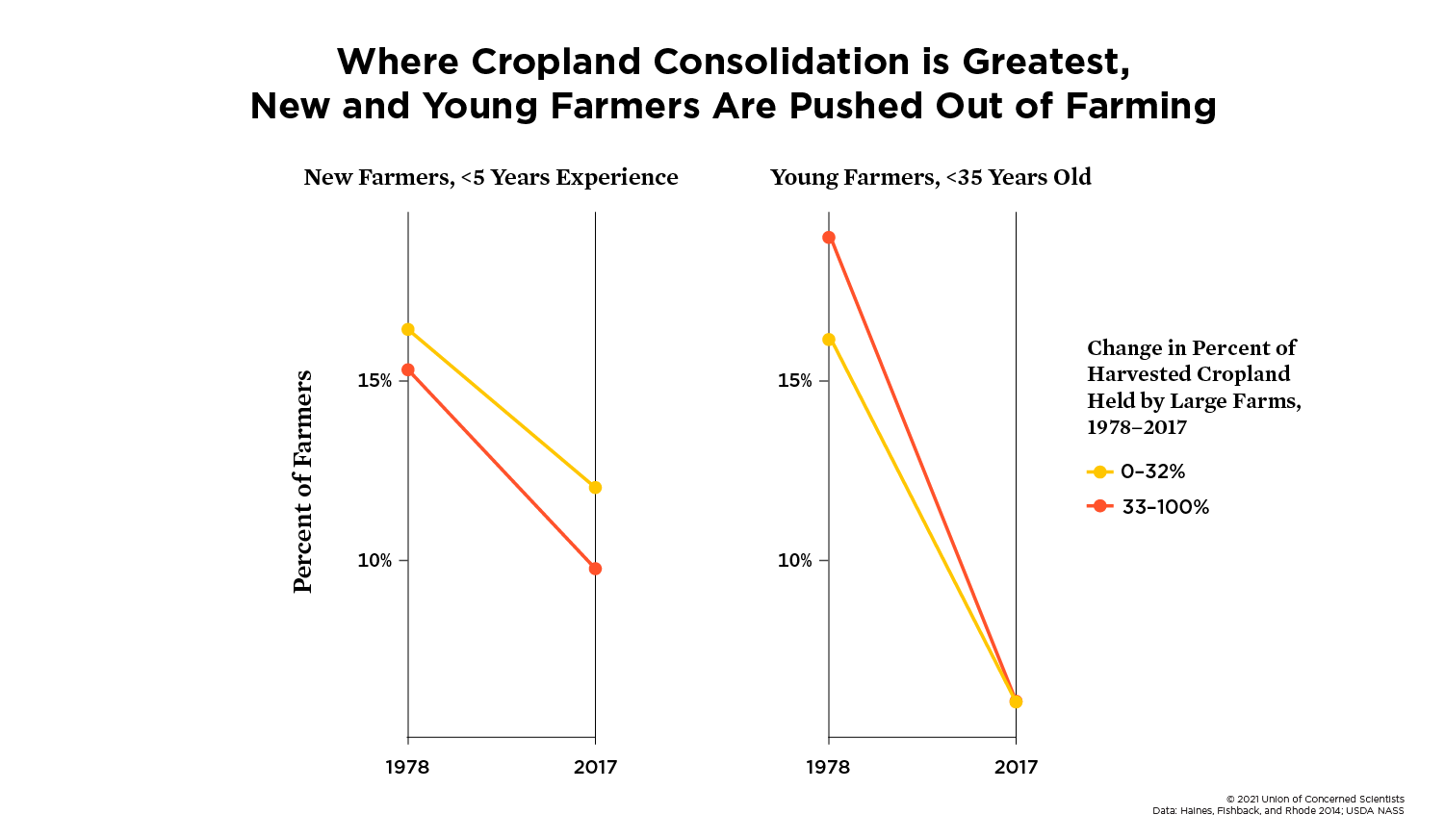

There are multiple reasons why we should be concerned about increasing consolidation. For one thing, larger farms mean that fewer people can be farmers. Consolidation operates to make farming a more exclusive club—and this has the largest impact on groups that are already underrepresented.

Our study focused on how consolidation may be driving exclusion from farming for two populations: new farmers, focusing on the Midwest, and Black farmers, focusing on the 16 states with the largest number of Black farmers in 2017.

Barriers to new farmers (and new ideas)

The energy, innovation, and initiative that new practitioners bring are crucial to the future of any profession—and farmers are no different. Our food system is going to be facing huge challenges over the coming decades, and we need an expanding, diversifying, creative community of farmers to meet those challenges. Consolidation operates in exactly the wrong direction.

During the study period, the proportion of new farmers in the US fell, and the average age of farmers rose—especially in the Midwest, where the proportion of new farmers shrank by nearly one-third and their average age rose by a decade.

Both trends were more pronounced in counties where consolidation was happening fastest: in these counties, the share of new farmers declined 56 percent faster, and average farmer age rose 26 percent faster.

Barriers to Black farmers

Farmland in the United States has always been highly concentrated among White male farmers and owners—but this has gotten worse, not better, over the past century. In 1920, Black farmers made up 14 percent of all US farmers. By 2017, that figure had shrunk to 1.6 percent.

The same economic pressures that drive consolidation for all farmers have affected Black farmers as well. But systemic racism has amplified these pressures through discriminatory policies and laws. In one example, laws governing “heirs' property”—an informal system in which land is passed down through generations, often to multiple family members in common, without a will—often left Black farmers without clear title to their farmland, restricting their access to credit and federal farm supports and leaving them vulnerable to losing their farms. But heirs' property is just one of the ways that Black farmers have been dispossessed, and the many decades of systematic discrimination by the USDA are well documented.

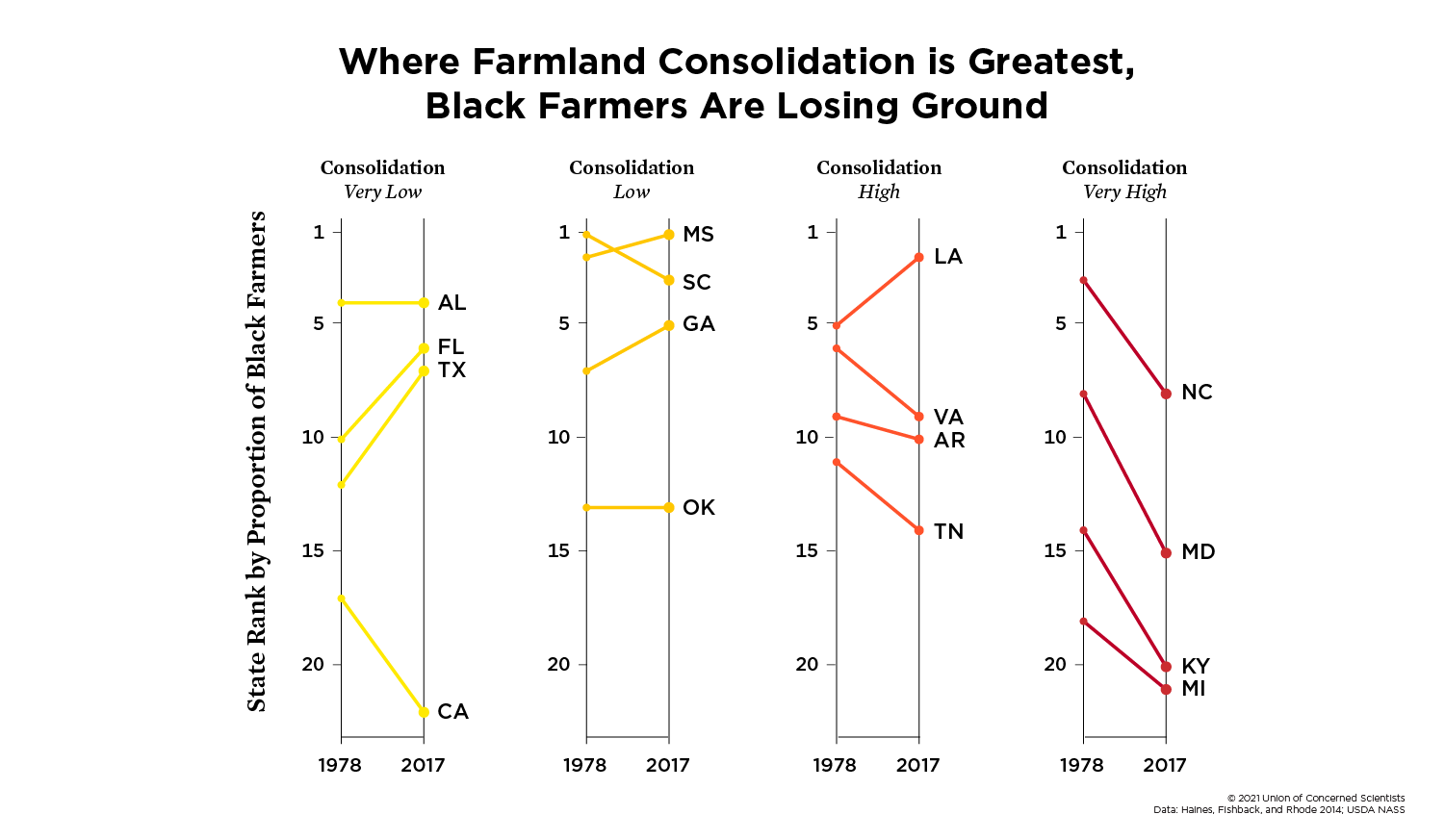

To see the impact of farmland consolidation on Black farmers, the study looked at the association between rates of consolidation and how states ranked in proportion of Black farmers. States with faster consolidation tended to fall in those rankings, indicating Black farmers in those states are losing ground fastest.

Why it matters: human and environmental impacts of consolidation

Access to farmland is access to political and economic power. When this power is concentrated in the hands of a small segment of the community, the community suffers: jobs disappear, population shrinks, physical and social infrastructure weakens.

Historically, midsize farms have been the foundation of healthy rural communities. The decline of these farms in favor of larger ones has been called the “hollowing out” of US agriculture. Research has shown that more midsize farms mean more equitable distribution of income, more money circulating in the local economy, more civic engagement, and a healthier community social fabric.

The land itself feels the consequences of consolidation: growth in farm size is associated with landscape simplification, in which large-scale monocultures replace natural vegetation and more fertilizers and pesticides are required, degrading soil health and increasing vulnerability to erosion and climate impacts. Because more farmland in larger farms tends to be rented rather than owned, there is less incentive to invest in measures to improve farmland for the long term by building soil health.

In short, when farms grow bigger and farmers grow fewer, bad things happen.

Growing Economies

Safeguarding Soil

What we can do: the role of farm policy

Because the drivers of consolidation are so complex, we need a coordinated national policy effort to address the problem.

Our analysis offers a detailed list of recommendations, including initiatives to support the next generation of farmers, assessment of policies related to market reforms and commodity pricing mechanisms, and legislation to redress the harm inflicted on Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC) farmers by past centuries of discrimination.

Ultimately, we all have a stake in the economic, social, and environmental well-being of our nation’s farming communities. Reversing the trend toward farm consolidation is a crucial step toward building a healthier, more equitable, more resilient food system.