Table of Contents

Investing in technologies that increase the fuel economy of America's vehicle fleet will create domestic jobs, save consumers money at the pump, cut global warming pollution, and put us on a path to cut projected US oil consumption in half over the next 20 years. Increasing fuel economy—a measure of how far one travels on a gallon of fuel (mpg)—is not a silver bullet. Yet, sound fuel economy policy and good engineering can deliver the cleaner and more fuel-efficient cars, trucks, and SUVs we need to help tackle our oil consumption and climate change problems.

History of US fuel economy standards

Congress first established Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards in 1975, largely in response to the 1973 oil embargo. CAFE standards set the average new vehicle fuel economy, as weighted by sales, that a manufacturer's fleet must achieve.

Through the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975, Congress established fuel economy standards for new passenger cars starting with model year (MY) 1978. These standards were intended to roughly double the average fuel economy of the new car fleet to 27.5 mpg by model year (MY) 1985.

Additionally, the Department of Transportation set the first round of CAFE standards for light trucks (i.e., pickups, minivans, and SUVs) beginning with MY 1978. CAFE standards for light trucks were increased to 22.2 mpg for MY 2007 and scheduled to increase further. No similar increases were made for passenger cars until 2007, when historic energy legislation was passed by Congress and signed by the President. This new energy legislation, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, raised the fuel economy standards of America's cars, light trucks, and SUVs to a combined average of at least 35 miles per gallon by 2020—a 10 mpg increase over 2007 levels—and required standards to be met at maximum feasible levels through 2030.

Federal law directing increases in fuel economy became necessary because oil consumption had been steadily escalating, in large part due to the relative stagnation in CAFE standards, the doubling of annual vehicle miles traveled in the previous 25 years, and a sizable increase in the market share of less efficient SUVs and light trucks.

In 2009, a historic agreement between the Federal Government, state regulators, and the auto industry established a national program to implement these first meaningful fuel efficiency improvements in over 30 years and the first-ever global warming pollution standards for light-duty vehicles.

The agreement grew out of the new fuel efficiency standards passed by Congress in 2007, the Supreme Court’s decision in Massachusetts v. EPA, which precipitated global warming pollution standards for vehicles under the Clean Air Act, and global warming pollution standards enacted in California and subsequently adopted by 13 other states and the District of Columbia. The agreement provided a mechanism for automakers to build a single national fleet of new vehicles that are in compliance with federal and state requirements under both the Clean Air Act and the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) program.

While each regulatory agency with legal authority promulgates and finalizes separate standards, the National Program harmonizes the three requirements. This is achieved by coordinating the rulemaking process and promulgating final standards that ensure that automakers can build a single fleet which complies with all three standards.

The National Program is comprised of three legal authorities:

- Department of Transportation (NHTSA): The first CAFE standards were administered by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), a part of the US Department of Transportation. As a result of the 2007 energy legislation, NHTSA is required by statute to set fleetwide average fuel efficiency standards for each new model year at the maximum feasible level.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): The EPA is required to set pollution standards for new light-duty vehicles under section 202 of the Clean Air Act. Specifically, EPA is required to set standards at a level that protects public health and welfare. EPA successfully implemented automobile pollution standards covering smog-forming, toxic, and other emissions for decades. Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Massachusetts v. EPA that greenhouse gases are pollutants under the Clean Air Act and the subsequent finding that those gases endanger public health, the agency was required to set global warming pollution standards for vehicles under the Clean Air Act.

- California Air Resources Board (CARB): When the Clean Air Act was originally enacted, Congress provided the State of California unique authority to set vehicle standard that are more stringent than the federal standards. California enacted legislation in 2002 directing CARB to develop global warming pollution standards for light-duty vehicles, which were finalized in 2004. Other states are able to adopt the California standards in lieu of the federal standards under section 177 of the Clean Air Act. Currently, 13 other states and the District of Columbia follow the state standards, representing nearly 40% of new vehicles sold in the United States. These states are required to adopt identical standards to those established by CARB, ensuring that there are just two alternatives — a baseline federal requirement and a stronger state requirement — instead of multiple standards.

Phase I of the National Program: Model Year 2012–2016

The first phase of the National Program was finalized in April 2010 after a 12-month regulatory process. The 2012–2016 standards were supported by automakers, state regulators, the United Auto Workers (UAW), environmental organizations and other stakeholders. Overall, phase I of the National Program represents a 23 percent improvement in new vehicle pollution standards, an average annual improvement of nearly 5 percent.

The EPA established global warming pollution standards of 250 grams per mile, on average, for model year (MY) 2016 vehicles. NHTSA set fuel efficiency standards which target a new vehicle average of 34.1 miles per gallon in MY2016. These two standards reflect a harmonized level of stringency. CARB agreed to accept compliance with the National Program as compliance with its standards even though the federal standards are weaker until 2016.

Phase II of the National Program: Model Year 2017–2025

Building on the success of the first phase of the National Program, the second phase of fuel economy and global warming pollution standards for light duty vehicles covers model years 2017–2025. These standards were finalized by the US Environmental Protection Agency and US Department of Transportation in August 2012.

These new standards will reduce average global warming emissions of new passenger cars and light trucks to 163 grams per mile (g/mi) in model year 2025. This is equivalent to 54.5 miles per gallon (mpg), if the standards were met exclusively with fuel efficiency improvements 1.

Benefits of Fuel Economy Standards

These standards will reduce America’s consumption of oil, save consumers money at the gas pump, and protect public health and the environment by curbing global warming pollution. They will also help spur investments in new automotive technology, creating jobs and helping sustain the recovery of the US auto industry.

- Oil Consumption: Nearly doubling the average fuel efficiency of new cars and light trucks is the single biggest step our nation can take to reduce oil use. When taken together, the two phases of fuel economy standards will result in oil savings in 2030 of more than 3 million barrels per day. This is roughly equivalent to the US imports from both the Persian Gulf and Venezuela combined.

- Jobs: A June 2012 study by the Blue Green Alliance finds that the second round of standards alone will create an estimated 570,000 jobs (full-time equivalent) throughout the US economy by 2030, including 50,000 in light-duty vehicle manufacturing (parts and vehicle assembly).

- Environment: The two rounds of standards will reduce global warming pollution by as much as 570 million metric tons (MMT) in 2030. This is equivalent to shutting down 140 typical coal-fired power plants for an entire year.

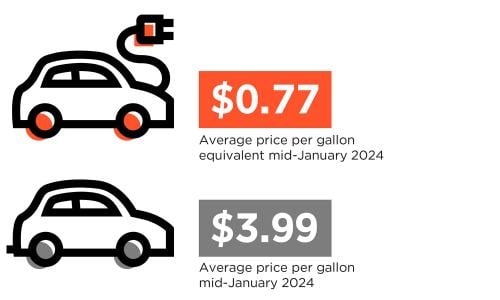

- Consumer Savings: The standards will save consumers $140 billion in 2030. When compared to a typical vehicle on the road today, a new car buyer will save more than $8,000 over the lifetime of a new 2025 vehicle, even after paying for the more fuel-efficient technology.

Notes:

- The actual Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard is expected to be about 49.6 mpg in 2025, with the remaining 5 miles per gallon equivalent reached through improvements to in-car air conditioners (better efficiency, reduced leaks, and use of refrigerants with a lower impact on the climate). Because CAFE compliance tests are out of date and overinflate fuel economy, the average on-road fuel economy of new cars and light trucks is expected to be 36-37 mpg by 2025. By comparison, the average of today’s on-road fleet is 21 mpg. See the UCS fact sheet Translating New Auto Standards into On-Road Fuel Efficiency for more information.