Chris Borland looked like he would have a lucrative career playing football. At the University of Wisconsin, he won the Big Ten Conference’s Defensive Player of the Year award and was named to multiple All-American teams. As a rookie with the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers in 2014, Borland led the team in tackles—then suddenly quit football for good.

What went wrong?

Chris had become concerned about the number of concussions he had sustained over the years, the risk that they could lead to permanent brain damage, and the NFL’s history of sidelining the science around its players’ brain injuries.

Science has linked repeated brain trauma to a disease called CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy. CTE can lead to memory loss, aggression, impulse control problems, depression, dementia, and suicide.

In studying the brains of 111 deceased NFL players, researchers at Boston University found signs of CTE in all but one. But for many years the National Football League denied there was any connection. Chris’s willingness to talk about the issue got him branded “the most dangerous man in football” by ESPN. Now he’s a science champion with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Chris Borland on working with UCS:

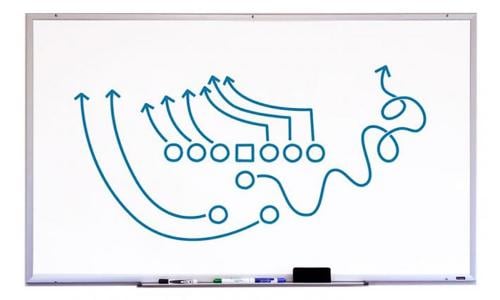

"Most simply it’s about truth. The Union of Concerned Scientists is showing with its Disinformation Playbook that many industries use the same tactics to sideline science, and pro football is a pretty clear example. The NFL has been trying to sow doubt about the science behind brain injuries, which for me is especially sad when you think about the fact that there are five-year-old kids out there playing tackle football.

"The decision for me to walk away from the game I’ve devoted my life to and become an advocate was not an easy one. In training camp before my rookie season with the San Francisco 49ers, we were hearing the tragic stories of players like Junior Seau and Dave Duerson, and it made me wonder “What’s going to happen to me if I play this game for a long time?” So I spent the entirety of that season reading about the issue, and finally made a pragmatic decision to protect my health. I was uncomfortable at first being cast in the role of an advocate, but I see the value in it, and in what the Union of Concerned Scientists is doing.

"I think I’ll always miss football, but I won’t miss the pain. I want to minimize players’ exposure to debilitating injuries—especially kids. When you ask former players “Would you do it all over again?,” they almost always answer yes, but you might get a different answer if you asked their spouses or children or siblings. Brain injuries happen not only to the players but also to their families and caregivers. The costs are high, and the NFL has made a lot of money while passing the costs on to the players, their families, and their communities. We need to stop this from continuing—in football and in other industries—by standing up for science with groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists, which works to ensure that science doesn’t get sidelined from decisions that can put our health and safety at risk."

The science on the link between repeated brain injury and CTE

The first case of CTE affecting a pro football player was discovered in a postmortem evaluation of former NFL star, Mike Webster, by pathologist Dr. Bennet Omalu at the University of Pittsburgh in 2005. Since then, neuropathologist Dr. Ann McKee, director of the Boston University CTE Center, has worked with Dr. Robert Stern, Director of Clinical Research at the BU CTE Center, and former wrestler Chris Nowinski, Ph.D., CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, to collect donated brains of former athletes and veterans and evaluate them for signs of the disease. The VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, a collaboration between the Veterans Administration, Boston University and the Concussion Legacy Foundation, now holds more than 400 brains and has diagnosed more than 70 percent of the world’s CTE cases. The Boston University CTE Center, part of the Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center established in 1996 by the NIH, is the lead institution conducting research on CTE and chronic health impacts related to repeated brain trauma in athletes and individuals in the military.

According to the BU CTE Center, symptoms of CTE include memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, impulse control problems, aggression, depression, anxiety, suicidality, parkinsonism, and, eventually, progressive dementia. In exploring the clinical manifestation of CTE, Dr. Stern and his colleagues found that “a triad of cognitive, behavioral, and mood impairments was common overall, with cognitive deficits reported for almost all subjects.”

In a 2017 study of the brains of 202 deceased football players, BU researchers found that 87% had signs of CTE, including 110 of 111 former NFL players. They also found that, “Among 27 participants with mild CTE pathology, 26 (96%) had behavioral or mood symptoms or both, 23 (85%) had cognitive symptoms, and 9 (33%) had signs of dementia. Among 84 participants with severe CTE pathology, 75 (89%) had behavioral or mood symptoms or both, 80 (95%) had cognitive symptoms, and 71 (85%) had signs of dementia.” Cognitive symptoms included issues with memory and language, while behavioral symptoms included anxiety and paranoia.

Unfortunately, researchers have been so far unable to diagnose CTE in living patients, however, the latest research out of BU suggests that a test could soon be developed using the protein CCL11 as a diagnostic biomarker. Longitudinal studies that follow youth football players throughout life will be incredibly helpful in furthering scientific understanding of the development of CTE. While there is little knowledge about CTE development in adolescents, a 2017 study coauthored by the BU clinical research team found that participation in youth tackle football before age 12 increases the risk of behavioral issues like impaired mood and cognition later in life. This builds upon a 2016 Wake Forest University study that found measurable changes to the structural integrity of the brain, due to repeated subconcussive hits, after children aged 8 through 13 played one season of youth football.

Resources on CTE Science

For more information on the leading science on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, check out these resources:

- Boston University CTE Center: Frequently Asked Questions about CTE

- Concussion Legacy Foundation: The Science of CTE , The VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank

- Brain Injury Research Institute: Understanding Our Scientific Research