In the first part of this special Clean Transportation mini-series Jess talks with Adam Browning of Forum Mobility about the future of heavy-duty electric trucks.

Transcript

New year, new you. It’s our annual reminder to resolve, reflect, and renew. Maybe this year you resolved to live a cleaner, greener life. You might have committed to taking public transit, to biking more, to supporting environmental organizations financially or via volunteering. If you’re taking any of those steps, THANK YOU. When so much of the environmental news seems grim, it can be easy to forget that each of us is capable of real impact. After all, corporations are made of people and many of those people would like to help make the world a better place.

Now speaking of the time of year, we’ve just wrapped up the busiest retail season. So much of these holidays is focused on gifts – giving, buying, receiving – and we often don’t think about how those items get into our hands. Before we can go shopping we have to have shipping, and a huge portion of those goods arrive in the US by water. Once the shipping containers holding all of our Furbys and Barbies and ugly sweaters are unloaded at ports, they’re moved again…and often by heavy-duty diesel trucks.

The problem with all those goods on all of those trucks is that they aren’t clean. Quite the opposite, in fact. Heavy trucks are massive polluters, and cause tremendous harm to anyone who lives or works near heavy truck transportation hubs. Everything from heart disease to asthma to cancer, and even premature births AND deaths can be connected to air pollution from vehicles like these.

People nearest ports and heavy truck routes are often lower-income, and frequently are communities of color or immigrants. The need to electrify our country’s trucks is urgent as our climate crisis runs into our online, on-demand shopping and shipping culture. Me buying moisturizer online shouldn’t shorten the lifespan of someone living near the port of Los Angeles.

Since I always want to give you, our listeners, rays of light amidst the doom and gloom, I’ve declared January to be Clean Transportation month here at This Is Science. Today’s episode starts with – surprise – corporate efforts to green our country’s fleets. Yes, you heard that right. Even corporations see the need to do better now that we know better. It's time to put the pedal to the metal and in the words of Rihanna: shut up and drive.

I’m your host Jess Phoenix, and this is science.

Jess: Today's conversation is with Adam Browning, the Executive Vice President of Policy for Forum Mobility, a startup company that's working to electrify trucks that transport goods from ports to locations relatively close by. It's a type of trucking known as drayage. Forum is creating charging hubs for these heavy-duty electric trucks, and they're also offering electric trucks on lease to drivers. Now, with the majority of California's drayage fleet driven by individual people who own their trucks, making that state-mandated switch from diesel to electric trucks is a huge challenge, as well as an environmental and economic justice issue. Adam, thanks so much for speaking with me today, and I'd like to start by explaining the scope of the problem you and Forum are trying to help solve. So if you want to give us some facts about the state of shipping. goods and materials today, that would be great.

Adam: Sure. Well, first of all, thank you for having me here. I'm excited to spend a little time talking about a subject near and dear to my heart. You can call it, you know, electrifying drayage or, you know, pull back a bit like this is the pointy end of the spear on how we get to zero emission freight across the board. So yeah, Forum Mobility is focused on this particular segment of the heavy-duty freight called drayage. We do this, you know, this was really catalyzed by the California Air Resources Board, who has passed some broad regulations that will, you know, by 2050 eventually get a transformation of all freight to zero emissions. But it singled out drayage for an intense early focus. And that's because, I think, a couple of reasons. One is the impacts on our port communities. Like, these are big, heavy-duty diesel trucks that go in and out of ports right next to a lot of people, and the impacts are not trivial. And then secondly, this is a segment of freight that is seen as potentially, you know, easiest to transition in that they're generally short haul around 100 or 200 miles a day, and it's a hub and spoke. Generally, this fleet goes out, does its business and comes back. And that is easier to figure out charging rather than, you know, over the road where you're going from Oakland to Chicago and every night in a new place. So in California, there are about 33,000 trucks on the drayage registry. So these are your class eight semis. These are your big rigs. And starting January 1 of 2024, if you want to bring a new truck on that registry, it has to be zero emission. By 2035, the entire fleet has to be zero emission. So this is a huge transformation. This is like a generational shift equivalent to our horse and buggy days going to the internal combustion engine. And we're, you know, just to provide a little more context, like this year, there are less than 200 zero-emission class A semi trucks on the road in California. And soon, we have to go to the thousands and then the tens of thousands in a really relatively short period of time.

Jess: That is a massive undertaking. So that segues perfectly into my next question for you, which is how on earth are all of these fleets and then individual owner-operators, how are they supposed to make this work? I mean, aren't electric trucks more expensive to purchase upfront than diesel?

Adam: Yeah, there's a couple of pieces to the puzzle here. And one you hit on right now is like in drayage, about 80% are independent owner-operators. These are generally pretty small shops. It’s “Jess’s truck,” not necessarily “Jess’s Trucking.” And they're generally driving very old vehicles. And they are often, you know, not well capitalized with a ton of resources. Another part of the challenge, of course, so is that this is nascent new technology. The trucking industry has known this is coming from a very long time and it's had a lot of time to prepare. Yet, just like your passenger vehicles, like, you know, five years ago, there wasn't, besides Tesla, there wasn't a ton of options. And it is really sort of nascent technology for the truck manufacturers. Then the third piece of this puzzle here is the fueling infrastructure. So this zero-emission doesn't necessarily, you know, equal battery electric trucks. It could also be the hydrogen fuel cell. I will say the technology for the trucks and the fuel availability for the battery electrics is much more ready for the battery electric rather than the fuel cell, but you're spot on. These trucks are very expensive. They are much more costly initially.

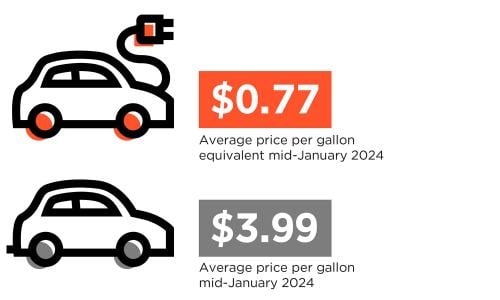

Now, the flip side here is that the prognosis and the prospect for bringing down those costs are very good. As we've collectively scaled up electrification, the amount of money that is going into new battery technology and new battery manufacturing capacity is mind-boggling. And so we do expect that there's a much longer-term future of significant cost reductions. And the electric trucks are cheaper to maintain and cheaper to operate the fueling. And there is also policy support for bringing down the costs of fueling as well. So the hope is, is that you can provide a trucking solution that competes favorably with diesel. And I'm happy to say that with incentives, with the subsidies that California has pulled together in California, we are able to make a, provide a truck or a charging experience that is in the ballpark of diesel operations. The goal then, of course, is to be able to provide that as the incentives gradually roll off, that you have a market transition, and that you're able to continue this at a cost discount. We define success as clean air for our communities, a safe climate, and lower cost per mile for truckers. I do think that, you know, long experience in climate tech and nothing succeeds unless it makes people's life better from day one. And that's the entire enterprise here is, like, how do you provide this transformative technology in a way that gets buy-in from all segments by being lower cost by delivering a better product right out the gates?

Jess: It’s a very admirable set of goals. And so I do want to dig in a little bit to the electric truck itself because I read from your company's website that Forum is also leasing out actual trucks. So it's kind of this one-stop shop model that Forum is offering. So you've got the trucks, the charging access, and the electricity. So I want to go into the whole package a little later. Right now, I just want to say, okay, what is the performance of an electric truck like? How is that different? I know what the difference between my Chevy Volt and my Chevy Blazer, which is an internal combustion engine car. I know the difference between that performance is significant. I mean, there's the more torque, it's quieter, and it feels like a spaceship still. So what is that? What's the range on these electric trucks? What's the in-cab experience? I mean, just give us the scoop.

Adam: Sure. So, you know, we have our first customer, our pilot project down in Long Beach, he initially, we built a bunch of charging at his site and bought three different truck manufacturers, a total of four trucks. He's since added to it, which is awesome, as this experience has been a good one so far and we can go into the reasons why. But we have, again, three different brands of trucks that we're running over the past nine months, around 100,000 miles so far, doing daily service in and out of the Port of Long Beach and out to distribution centers. And so, you know, similar to your EV, you know, there's a whole range of different models with different performance characteristics out there. You can buy a Leaf with 100 miles or you can buy, you know, the long-range Tesla with 300 plus. The trucks that we have, we've got some BYDs that are about 150-mile range, and then some Volvos with a little over 250-mile range, which is absolutely sufficient for the use cycle, the service that they are doing, again, in and out of the Port of Long Beach every day. The, you know, power is great. The torque is great. The drivers, let me just really drive in on this, love the vehicles.

And so, sure, it's different. You've got to think about your charge capacity. You have to plan ahead for how far you're going to go. The trucks are heavier. And so, there are weight limits on roads. So, you have to think about, you know, the weight of the container. But the actual day-to-day experience, one of our customers' drivers, Javier, told me, he's like, "Look, my other truck, it had, you know, 13 gears on that." Like, try thinking, you know, clutching through, like, rush hour traffic on the Harbor Freeway, you know, pulling a load.

Jess: Yes.

Adam: And he's like, "The electric truck is one-pedal driving." And he's like, "My hip, my knee has never felt better. It is, like, just a lot less hard on the body." People talk a lot about the noise and really the vibration as well. It is just, again, it is like the electric vehicles. It is a quiet, vibration-free, smooth experience with one-pedal driving. And trucking can be hard on the body with a huge diesel engine that's rattling away, the noise, the fumes. So when you get truckers driving them, again, people have to think a little bit differently about the service. But the actual experience is, I haven't talked to a single person who didn't love it.

Jess: That's incredibly neat. And your mention of the impacts on the driver's bodies, I remember reading a study about that probably 20 years ago about how hard, like especially long-haul trucking, is on the people who drive the trucks. And I personally have a couple of friends whose fathers are individual owner-operators, and one of them does long haul, one of them does drayage. And it's a rough job. And so moving from acknowledging that the way we ship stuff now is not ideal, tell us about the impacts that electrifying these drayage fleets, what's that going to have? What kind of an impact is that going to have on the communities who live right near the ports?

Adam: Again, this is one of the big reasons and the rationales for why we urgently need this type of transition. You know, the emissions, it's not just the carbon, it's also the particulates and the... But if you look at the statistics around port side communities, Wilmington in the Los Angeles area, cancer and asthma incidences are double than in communities that are farther away from all that traffic. So, these are non-trivial sources of emissions that do have really negative impacts on human health and the environment. So, going to zero-emissions, so, you know, we fuel these with renewable electricity. You can procure those through our community choice aggregators or through SoCal Edison. Going forward, we'll also move to a community solar model once we get those rules and regulations moving forward in California too. So the initial premise here of, like, we need to move to this to protect human health is crucial.

The other part of this is really also the climate concerns. And so I think you need to think about this not just as the emissions that come from this particular segment, drayage, but this is where we incubate and mature the technologies that are also going to be helpful for a much broader range of freight across the board. And this is how we catalyze the manufacturers to put in the R&D, to build the production capacity, to build the technology. This is how we start the build-out of all the charging infrastructure. And it's not just your short-term impact on climate emissions. It's about how do we go about transitioning the entire freight sector. And again, this is the first building block, the beachhead, if you will.

Jess: Yeah, I think that's a really good way of putting it because this is a huge problem. You know, just the whole planet is wrangling with how do we have a good climate future and still improve quality of lives and then maintain what we have in certain instances. So it's interesting to me that Forum is kind of providing everything from the tool in the truck to the fuel, which is the electrification, you know, of the charging stations. So you get the ability to refuel and then you're also giving them the fuel through the companies you mentioned or, like, Southern California Edison, for example. I work for a nonprofit here. UCS is an NGO, but is this a model that is going to work for a for-profit startup? Is this something that investors get really excited about? Because it sounds like you guys are taking a lot of risk upfront and then to build the infrastructure, to lease out the trucks. Do you think this is going to be something that's sustainable and profitable for Forum and other companies that are similar? Adam: Yes, I do. And, you know, this has been the entire sort of theory of the case. My last 20 years was in solar and our focus there was there was a really niche technology that few took really seriously. It was incredibly expensive. It was a rounding error in the overall scheme of things. But the sum total was that it had some incredible advantages that if you could bring to scale and bring down costs, you could end up with a situation where it was an economic benefit. And our theory was, like, through scale, you brought down costs. And so last 20 years, that was the story of, right, you know, and now solar is the cheapest and fastest-growing source of new generation globally that there is bar none. And I would argue the foundation of our hopes and the fight against climate change. So if you're looking for this transition also on mobility and specifically on freight, I think there is a similar opportunity that stuff's pretty expensive to begin with, but through scale, you can actually bring down those costs and you can get to a point where you have a service that ends up being both better and cheaper in the long run and the long term.

So, right now, our model, again, is to build these charging depots. And we provide charging as a service, so charging for a monthly fee. If you have your own truck, you bring it, or we will provide a truck plus charging together, and our goal is to get that around diesel parity. I would just put a note here. We would rather just do charging. It's a lot more simple. And we are involved in purchasing and leasing the trucks because the initial customers need that. They want that. They ask for that. Long term, that probably won't be our focus. That's where the truck manufacturers hopefully will be able to provide that service at scale and at a lower cost, and we will be able to do it. But right now, we will do whatever it is that our customers need in order to get this moving. Jess: Something you touched on earlier was the government incentives. And obviously, when we had low-emission or zero-emission vehicles previously in California, where you and I are, the government would provide access to the high-occupancy vehicle carpool lanes, or they would give you tax incentives. You know, here's $8,000 off for getting one of these cars, leasing it, or buying it. So how are government incentives? How are they helping the switch to electrifying heavy trucks? And then, like, is there a time limit on those incentives now that you're working under?

Adam: Sure. So when you're looking at, you know, transport and trucking, like, there's a couple of different ways that money can enter the system to help bring down your collective total cost of ownership. So you can have incentives for the vehicles themselves. And so the California Air Resources Board does provide some direct incentives through a program called HVIP. I struggle to know exactly what that acronym is right across the top of my head. And so there is a small federal tax credit for it if you can actually utilize it. There are the other part of the challenge is building the infrastructure. So building charging infrastructure, depots, the actual chargers themselves, all the wiring, the interconnect to the distribution grid, the land, all that can be quite expensive. And so the California Energy Commission does provide a limited amount of incentives on a competitive basis. Some of the air districts also on a competitive basis have limited funds to help support the initial depots on this. And there is also a federal tax credit for that. Again, not transformative, but we won't turn it down either. And then you can also provide incentives for the fuel, the charging itself. And so, you know, on the hydrogen side, if you're looking at a hydrogen fuel cell, you know, there's a huge federal incentive for this that they're all figuring out how to deploy as we speak. On the electricity side, it's state-level policy. And we have something in California called the low-carbon fuel standard, which essentially provides, like, a downward trajectory on the carbon intensity of the fuels that get sold into California. And so if you have a high-carbon fuel like gasoline, you need to buy offsetting credits of low-carbon fuel. So in essence, we will be selling or are selling low-carbon credits to gasoline sellers, and that will provide another revenue stream that helps offset the cost.

Some of these are much more durable than others. Like, those truck incentives, like, there's not a long-term plan for this. There's not, you know, a 10-year ramp-down on it. And on the low carbon fuel standard that is a much more durable program that we believe will be really crucial into providing incentives for keeping the cost of fueling as low as possible.

You asked about risk earlier and I think that frankly is the area of one of the highest risks is, like, how do you, of the different programs, how do you bundle together, like, enough to, again, get to diesel parity. And how do you continue that in a way that you can grow your operations as you collectively bring down costs? Because, again, you know, all the chargers that we're putting in, like, you know, these are really high power chargers and they're from a bunch of companies that weren't doing this three, four, five years ago. They're in now and technology is moving quickly and there's a huge opportunity for continued cost reductions but we're on the very early part of that S curve.

Jess: I think one of the interesting things about talking about this with you and just thinking about how technology has changed just in my 40 almost 2 years on the earth, it's really different. And the thing that I keep noticing is that we have the technology. It exists. And it's all about just getting that adoption to be more widespread and to making it economically feasible and also just saying, "We got to get rid of the old and bring in the new." And you've been personally involved with solar, and then now this. How did you decide that your next step would be not solar specifically and moving into something that's really tangible in terms of how goods move? I mean, what made you make that leap over to Forum?

Adam: Back in 2002, I started a nonprofit called Vote Solar. And the focus was on developing the state-level policy to catalyze these early-stage solar markets to help grow market demand, to catalyze the building of new scale-up in manufacturing to bring down costs. That was our initial premise, and over 20 years of working in probably over 45 states. And the organization grew from being a buddy in a subleased office space in South of Market in San Francisco to where it is today. There's 45 lovely people working around the country and developing the state-level policy no longer under my leadership but under a very capable next generation of leaders. That effort was just the joy of my life, a really difficult but joyful ride, a lot of work and it worked, right? That initial premise of through scale, bring down costs and build the workforce and build the supply chains and of the future, you know, absolutely paid off on its premise. So after 20 years of doing that, I turned 50 and I was like, you know, if I'm gonna do something else, like, my timeline is getting shorter. I better start doing it.

It really also felt like it was time to give other people the opportunity for the best job in the world. It felt like I wanted to build some new muscles and have some new experiences. So I stepped down. I didn't know what I was going to do. And I spent some time thinking about it. And I did a little consulting. And I knew I wanted to stay in climate. And I knew I felt like if I had any skill set, it was, like, thinking about what are the things that we know that we need but don't yet exist. And I will be honest that drayage wasn't on the top of my list. I had frankly never even heard of it. But some colleagues that I'd met 20 years ago in the solar industry had started this company called Forum Mobility. In fact, Matt LeDucq, the CEO, I first met on the roof of a solar install at Google. He was the foreman. He came up through the hands-on installation side. And so it just felt in a very similar space, that there was nascent policy, nascent technology, a huge opportunity to address what is considered a really hard-to-decarbonize segment. And I felt like this was a space that felt like solar circa 2002 and collectively that there was a huge opportunity to make a, to pull a very big lever and make a big change. So it's been a lot of work, but I'm really glad that I took a jump and am focused on this next segment.

Jess: Yeah, it sounds like you're pretty excited about it, and that's always good. We want people working on these transformative things who are really enthusiastic. So that's really great background, too. So we are the Union of Concerned Scientists here, and so I have a question I always ask my guests. And so for you, Adam, why are you concerned?

Adam: Thank you. Oh, man. I mean, for me, it's climate. I mean, there's a lot of threads that come into all of this, and it always has been very clear to me that we need to make changes in order for our species to continue to live in the climate that we evolved in. And losing that is not an experiment that we want to try. I have a young daughter. Yeah, it just gets personal.

Jess: My family, we adopted a really awesome teenager from the foster system, and I can't stop thinking about what the world is gonna be like for him long after we're gone. So I feel you right there. It's super personal. And I think that's what makes the work, whether it's nonprofit, government, for-profit, that's what makes it really meaningful.

Adam: Oh, you know, but I do want to just sort of shift as well to say that I feel like almost everybody, you know, wants to be working in a place and doing something that is larger than themselves, and all work is honorable. But it is especially, gratifying when you feel like you're doing something and working in a space again trying to achieve something that has a much more broad impact. And so, you know, I also feel very lucky to do this. And I spend a fair amount of time talking to people that are doing something else and want to get into climate because they crave a sense of job satisfaction that maybe they don't have right now. And so for those people, if they are listening, I would say, do it. The water is warm. I'm not sure if that's the...there's a joke in there somewhere, but jump in. And so if you're a lawyer, if you're a banker, and if you want to get in climate, do climate law, do climate banking. Take the skill that you have and make that switch. You won't regret it.