Biologist Dr. Monica Unseld details her journey from scientist to activist and discusses how science institutions can forge successful partnerships with communities.

In this episode

Colleen and Dr. Unseld discuss:

- how scientists can be advocates for underserved communities

- how bias influences data collection

- how she works with communities to collect and track local data

Timing and cues

Opener (0:00-0:23)

Intro (0:23-2:13)

Interview part 1 (2:13-14:32)

Break (14:32-15:24)

Interview part 2 (15:24-28:14)

Outro (28:14-29:00)

Credits

Editing: Omari Spears

Additional editing and music: Brian Middleton

Research and writing: Pamela Worth and Cana Tagawa

Executive producer: Rich Hayes

Host: Colleen MacDonald

Related content

Full transcript

Colleen: For many people who study science in higher education, there’s often a clear path to a career once they earn their credentials. Teaching, doing research, practicing medicine, or engineering—these are common and traditional ways to use scientific skills and knowledge.

My guest for this episode spent four years pursuing one of these traditional career trajectories, teaching at the collegiate level… before she realized she wanted to do something completely different. And she believes that more scientists and scientists-in-training can and should think outside of these paths… and that a passion for making the world better can align perfectly with skills and training in STEM fields.

Today, Dr. Monica Unseld is the founder and director of a Kentucky-based nonprofit called Until Justice Data Partners. And if the idea of using science for a better world sounds familiar… it turns out that she has a lot in common with the founders of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Like her, they were dissatisfied with what they were expected to do with their degrees. Like her, they saw the potential for scientists to be activists, and use their skills and expertise in service of the public good. And also like her, they started their own nonprofit to do just that. Dr. Unseld has done all of the above… while also navigating scientific spaces as a Black woman, and navigating Black and Brown spaces as a scientist and academic.

She joined me to discuss how data can make a difference… how science and academia can do better to support the people most affected by issues like pollution and climate change… and how sometimes, it’s okay to be petty for justice.

Colleen: Dr. Unseld, welcome to the podcast.

Dr. Unseld: Thank you. I'm so happy to be here.

Colleen: Excellent. So, early in your career, you saw the connection between the role of science and racial injustice and environmental injustice. When did you first make that connection?

Dr. Unseld: When I was in graduate school, my graduate advisor, Dr. Cynthia Corbitt, at the University of Louisville, her degree is in endocrine disruption and environmental signaling. And we would go to these yearly conferences in New Orleans called an E.Hormone. And that's when I first heard of Dr. Robert Bullard when I first heard him speak. And I first heard Dr. Tyrone Hayes speak. And it completely not only opened my eyes to the environmental justice movement, but to the idea that as a scientist, I can do more than just write peer reviewed journal articles, I can do more with the knowledge I have. And then in fact, I should be doing more.

Colleen: So is this when you decided to use your science and data to help communities suffering from the impacts of pollution?

Dr. Unseld: That's when I wanted to. That was a goal. However, I think, as many graduate students will tell you, we're kind of funneled into academia, or private industry and no one really talks about creating these spaces where you can do advocacy work, activist work, and still, hopefully, and potentially pay your bills. So while it was a goal in graduate school, I wasn't aware that it was possible, until I was asked to join the board of the Kentucky Environmental Foundation, which is now a new organization. But it was through there that I came into contact with environmental justice activists, and community groups and other scientists. And that really did...The light bulbs just went off where I thought, "Oh, I don't necessarily have to teach photosynthesis in order to do this work."

Colleen: So can you tell me about some of the projects that you worked on?

Dr. Unseld: Right now we're working on a campaign to get Johnson & Johnson to remove their talc baby powder off of the global market. I've been able to work on policy in terms of facilities, managing spills, shutdown procedures, emergencies. This past March, I was on an ad hoc panel for the EPA to revise and make recommendations on their fenceline screening methodology to determine whether or not their chemicals are dangerous and need more evaluation. I've done quite a bit I've gone and talked to government representatives their staff, policymakers, about the need to shut down some chemical facilities . I looked into the impact of tear gas on potential long-term health exposure dangers. I've kind of been all over the map. But you know what, it's been fun.

Colleen: There's no lack of projects to work on. It sounds like.

Dr. Unseld: Yeah, and unfortunately, that is true, right? Because justice is it's huge, this ball of tangled yarn, that has become a mess of oppression, and marginalization, and silencing, and genocide. So there really is room for everyone. I've even worked with some students here called Mighty Shades of Ebony, they're a hip-hop group. And we were able to get some graphics and some data together about trash collection and how parts of the City of Louisville are able to get rid of their trash more easily than others because there are more trash cans, and these wonderful young people were able to get trash cans decorated with this beautiful art. And then people who own trash companies are like, "Well, we may wrap some of our trucks just to raise awareness of how garbage is a justice issue." So I really enjoy the fact that on the one hand, there's never a dull moment, I don't get bored. But again, with any justice work it can be exhausting, and painful and emotional.

Colleen: Right. So how do you deal with the emotional aspects of the work?

Dr. Unseld: I have to remember that I'm not alone. Because I think sometimes especially the way that our society teaches us from a very young age, it's so rooted in individualism, that sometimes we feel it's our responsibility to solve the problems of the world by ourselves. And it's important to remember no, no, everyone has something to bring to this, everyone has a role. So don't try to pattern yourself off of someone else. And if you need to take a break if you need to rest, do that, because there are other people in this battle.

Colleen: So universities and research institutions don't have a great track record when it comes to working with communities to solve problems. What have you seen on the ground?

Dr. Unseld: I'm glad you brought that up, I don't always go into a community meeting as Dr. Unseld, I go in as Monica. One, because if I come in as Dr. Unseld, there may be a perceived power imbalance, or they may feel the need to defer to me when there's no need for them to defer to me. And also, as a Black woman, I know how harmful academia has been to so many communities.

one thing that I've had community members to say that was refreshing about me, is that I will tell them, "Yeah, academia can be horrible. Academia has a lot to apologize for." And I do have to call out my fellow scientists sometimes because we have been complicit. So, for example, the CDC has said, "There's no safe level of lead in children." But how many researchers are looking at threshold level exposures for lead in children? That question has been answered, there's no safe levels. So why are we still complicit in playing this threshold strategy, or even the concept of acceptable risk, we have normalized, the fact that some people dying is to be expected and that it's okay.

And so we're not even gonna make an intentional goal, to try to at least reduce the amount of acceptable risk, but hopefully eliminate it. I've been able to train some scientists to do this, which has been fun. It's just the way we speak. We can be very elitist, very arrogant, and we want to say that we're dumbing things down, we're not dumbing things down. It's just that we may think, so elitist and technical, in the first place, that the science is really of no use to anyone outside of academia, or private industry. And I believe science should have a service, you have this knowledge, we should do something with it.

So I've spoken with scientists about even the need to fluctuate your voice. I know we've all seen science presentations, or someone was very low volume and monotone. And it just really was difficult to pay attention. But for some reason, we've been told that that's what a professional speaker sounds like. No, especially for black and brown cultures, we normally don't rely on monotone voices, we are very expressive naturally. So I think we have to get out of our own way. And say, "Hey, speak like a normal human being. If you're passionate about it, be passionate about it."

Colleen: You can show your passion.

Dr. Unseld: Exactly, especially since we know with the limbic system that it is used in decision making. So this whole thing about you need to be unemotional. I mean, the science doesn't even back that up. So why are scientists perpetuating that myth?

Colleen: You talk in one of your blog posts about communicating uncertainty. And I think you're alluding to this a little bit, but can you tell us what the precautionary principle is?

Dr. Unseld: Yes. So to sum it up, in a very, very succinct, is that if we're not sure it's safe, let's sort of err on the side of being conservative, and maybe don't rush it out to put it on store shelves yet. You know, maybe we shouldn't use the approach where the product is on the market. And then enough people get sick for a class action lawsuit. Instead, we should say that we need to know if this chemical or this product is safe before., Who needs to continue being the guinea pig, right? And we know, unfortunately, that it's gonna be a lot of marginalized groups, people of lower economic status, but you kind of have to say that could be you one day, that could be someone you care about.

So who deserves to be the guinea pig here, while we figure out if this is safe or not? Or can we say let's just hold off before we put this chemical, and 20,000 new products over the next decade? And maybe let's make a goal to try to create safer chemicals. I'm kind of frustrated at the state of science in this country. I do not see the same urgency that was once there to get to the moon. And I think we were urgent to get to the moon because the President of the United States made it public. He publicly said, "We are going to the moon." And I haven't seen that commitment from policymakers and either party, local, state, federal level of just being intentional, like we're going to do better.

Colleen: Turning things around with science organizations is really hard. Have you seen examples of individual scientists working with communities, and does that model work better?

Dr. Unseld: Until science organizations can acquire some humility, and realize that one they've caused harm; two, they continue to cause harm; and three, that they have to learn and listen, I think we may have to rely on individuals. So I've been in meetings with certain scientific organizations, and they said, "Oh, let's look to this university for how to do community engagement." And I just was like, "No, absolutely not." Academia can't even make people of color feel safe on campus. Why in the world, would we go to them to help engage with communities, because I think, as scientists, and this came up here locally not too long ago, we tend to go to the library, before we talk to the community. Someone did some work on certain chemical exposure. And they talked to the more disproportionately impacted groups and gathered their data, when it came to creating a list of recommendations, instead of going back to the community to check in, they went to find peer-reviewed research.

And I said, okay, so we all know that by the time something's peer-reviewed, the peer-review process is going to maybe edit the life out of it, and two it's going to be a little bit delayed. And we know since COVID, that society is rapidly changing. And also it's harmful to extract data from communities, and then come back and say, "This is what other people recommend that we do in your communities." That's just, it's rude. And it creates and continues, the harm that academia and research has put on these communities. And then we wonder why they don't trust us. It's very frustrating, because I really feel like we have to take into account lived experience. That is data. It may not be peer-reviewed, right? It may not have the statistical power, we may not have a large enough sample size to get a p-value of any real meaning. However, it's going to tell us data gaps, it 's going to tell us questions that we perhaps should be asking. And it's going to keep the scientific process moving. We can't just keep operating in a void. And I think that's what we're doing. We have to trust that communities that have kept themselves sustained, and alive, over 400 and 500 centuries of oppression and genocide, that maybe they do know some things that work. And so before you go to the library, I tell people go to another zip code in your community before you hit that database.

Colleen: So do you have some good examples of scientist and community collaborations? I'd love to hear about something that worked really well.

Dr. Unseld: Well, here in Louisville. This was before I became a part of the environmental justice movement. The Star Program is Strategic Toxic Air Reductions. So the city of Louisville has control over its own air. It's not at the state level. And that's unfortunately because our air is so toxic, but it was rooted in community members who were going to city council meeting, metro council meetings regularly in providing comments and eventually they were able to work with the Air Pollution Control District. And they've created this program that we have local air monitoring. And it was because communities, they went and researched these chemicals. They went and researched the health impacts and that's another reason why dumbing it down really bothers me because there are communities who know far more about this than we do because they have to in order to survive. Colleen: Let's talk about data for a moment. Because there is a lot of bias in data. How do you ensure that you've got good data and the data that you need?

Dr. Unseld: I would say, if possible, I know this is not always possible, right? In terms of capacity and funding, try some ground truthing and go back and check with the communities. Because a lot of the existing data is bad. We've spent millions if not billions, on interventions based on bad data, because a lot of the data assumes several things. One is that the Western European, white supremacist model of society is the norm and everything else is a deficit. It's not seen as a difference. But it's seen as a deficit, something that needs to be fixed, right? And when we look at maybe black people aren't going to the doctor, as much as white people. And then all of a sudden, we're blaming black people, when really we should say, "Well, there's maybe some racism within the healthcare system, or there are not many hospitals, and the public transportation system is not good. Or there's cultural differences, or they don't speak my language." So we tend to turn it around and say, "Any difference is a deficit that needs to be fixed."

Another one is just we look at male bodies, right? How many times have you seen a drug recall or a study say, "We didn't know this would act differently in women." And you're sitting there and thinking about estrogen. Like that's a first potential hypothesis right there, right? And it really wasn't difficult to come to that conclusion, there are differences between estrogen and testosterone. And if all of these studies are picking volunteers and participants that are from certain economic backgrounds, and in order to clean the data, and to get a control group, and make it as clean and so that we can say it's scientifically rigorous, we end up omitting so much reality. And I always say that I think we're stuck in test tube science. And then we try to take those test tube findings and put it into society. And we think it's chaos, when really we need to examine how do we fit society into our models? Instead of saying, "How do we make society fit to our models?"

There's so much data, that's just bad. And I think a lot of people don't wanna hear that because it hurts, right? And some people are leaders in their fields. And you're just saying, well, you're assuming that this culture behaves in this way. Or you're assuming that they behave in a different way, because there's something wrong with them. And really, we need to say that people move through this world differently. And there's a lot that we can learn from each other. But we're never gonna get there. If we don't at least admit that in order to make things as clean as possible, we are making things a little bit if not a lot unrealistic. And I think I'm not saying I have a fix for that. But I think we should at least be honest

Colleen: So you founded Until Justice Data Partners, what is your vision for a more just and equitable way to approach data collection?

Dr. Unseld: Oh, wow. Because I mean, my ultimate vision is that my non-profit would no longer be necessary that I could close the doors. A lot of my work, and I think this is part of my vision is to normalize data. Normalize the fact that we all do research, it may not be graduate level research. But even there are a lot of people who started non-profits, right. And they started those non-profits because they are aware of an issue in their community. They did some research, and they planned an intervention. And to report to funders in the annual report, they have to collect data, and evaluate. There are so many researchers out there, but we will not give them that title again, because we've tried to be as exclusive as possible, thinking that that's the best way when really, we need to be as inclusive as possible.

So one of my dreams would be to just teach people how, well one, how they're already doing research. But how by using the scientific method, it can maybe make it a little easier. So a lot of the work I do with community partners, is I make sort of templates, where I break down the steps, and it kind of forces people to think in chunks like step one, step two, step three, which, as science, we all know, that's the scientific method, right? We know that there are steps to follow. But I think without that training, sometimes, we know that there's a problem that needs to be fixed, and it gets so overwhelming, that we feel like we can't do it. So you just quit.

So if I can help someone break it into thought buckets, and say, "Okay, so now we put it in thought buckets, but then this is how you put the buckets together into one ecosystem." I also try to encourage people to ask questions, and push back against government leaders against the media. So for example, Kentucky likes to say it's tough on crime. And I asked a panel, I said, "Well, what does that mean?" Because Kentucky, we have some of the harshest penalties in the United States, we have more people in prison than most of the United States. And so I said to this tough on crime mean crime prevention, or does it mean longer sentences? Because those are two completely different things. And people were shocked. And I said, "Well, who got to define it."?

And whoever got to define it all of a sudden gets to set off this narrative, or the fact that we have enough data to know that racism is real to know that it's a public health issue. And everyone wants more stories, they want more data, right? They want to bring in more consulting firms. They want to just paralysis by analysis, right? So I always say I said, "Well, one thing you can conclude from the data is that over the past 60 years, disparities have not decreased." So disparities have not decreased.

So one conclusion is that those who have had access to power and funds and the means to make a change so that those disparities do decrease, they may not be interested, or they don't know how, and perhaps they need to speak to other people and try something new. Because I think we get stuck in these patterns of, "Well, this is what we've always been doing. So we're just going to keep doing it." Or I say, "Listen, I don't want my non-profit to be around for 150 years. And I don't want it to be like in 200 years have to have it, you know, little franchise of it around the country, because that means that we weren't as effective as we had planned." Communities have expertise, your lived experience is expertise. But academia can teach you that I know more about your life than you do because I read a book about you. You know, but I have these degrees. So you should listen to what I'm going to tell you about your life, when you should really be telling me to sit down and be quiet.

And I think people are so conditioned to being quiet, that we have to say, "No, you have every right to be angry. You have every right to question, to ask a different question." You have every right to say, "Why have we only been collecting the same data points, but not the ones that will actually, you know, start solving problems So we have a lot of data that's not really useful. It's useful for like if you're trying to attract a corporation to come to your city, but it's not useful in tackling food insecurity. But the data that gets funded, the research that gets funded is not the research that's actually going to disrupt the system right?

Right now in the black community, there are a lot of business incubators that are getting a lot of money from funders. People working on justice issues, it's very difficult to get money, anyone who is trying to disrupt or is seen as trying to disrupt the status quo, can't really get money for that research. And people try to shy away like, "Oh, it's too political." When really it's all political. Whether the government steps in or whether the government sits it out, it's political.

Colleen: Well, is it safe to call you a scientist activist?

Dr. Unseld: Yes, I am not offended by the word activist.

Colleen: So what are your thoughts about scientists being activists?

Dr. Unseld: I think we need to be, I think if you have information that is going to help someone, then you absolutely have an obligation. And I think it's unfortunate that the term activist has been tainted, because being a black woman, every breath I take makes me an activist right? The system does not want me here, the system certain nly does not want me speaking to you. So I have no choice but to be an activist because my life's on the line. So when I went to a...it was a conference in grad school, and learn that for two decades, we knew that diethylstilbestrol was not helping prevent miscarriages, but it was making people sick. And I'm thinking, "Why weren't we screaming from 1950 to 1970? We should have been screaming, stop prescribing this."

So I mean, I feel like I never want to sit through a conference like that, again, where we're saying, well, we know this is bad. But then we're not out there telling people or unfortunately, there are a lot of journalists that write about science, but they don't understand the method. Or we saw it with the pandemic, right. They don't know that science can change. As we get more information. They just want something like final answer, but that's not how it works.

I tell some of my colleagues, get out of your lab and go into the community so that people can understand the scientific process. So we don't have to counter someone throwing up a YouTube video about their theory of COVID. Right? Look where it's gotten us, So I think we have a moral obligation to inform policymakers to inform the public to inform everyone of what we know, and how the process works. And if that means we have to learn how to speak in a less technical way, then that's what we need to do.

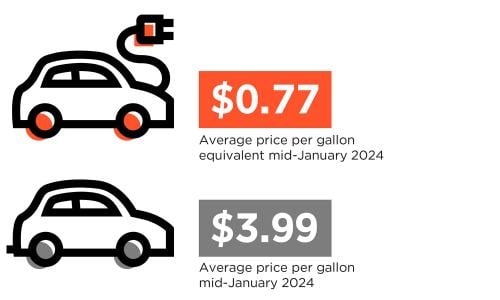

So I really feel like there's no excuse for anyone to sort of say that scientists should not be involved. That's not being objective, that's actually taking a side of the oppressive, the oppressive conditions, the oppressive status quo. So by sitting it out, it's one of the reasons why we are talking about gas prices, when really people are getting bombed. And we should be worried about that, right? There are people hiding in the shelters, but instead we're worried about gas prices, because we didn't say, "Hey, we can't do this anymore."

Colleen: Well, Dr. Unseld, first, I wanna thank you for the work that you do fighting for communities and really for seeking to change the system. It's really inspiring.

Dr. Unseld: Thank you. And I just want everyone to know like there's something you can bring to it. I promise you. I tell you, if you feel a disturbance about something, then you're being called to do something about it. If you're being called to do something about it, it's because you're capable of doing something about it. Even if it can be petty I can be extremely petty. And so my pettiness can sometimes pop up in writing a campaign toolkit against a company with some, like, throwing their own words back at them, right.

Colleen: Pettiness as power?

Dr. Unseld: Yes, petty for justice.

Colleen: That's great. Well, thank you so much. I really appreciate your taking the time to talk to me.

Dr. Unseld: Thank you. It's been fun.