The Union of Concerned Scientists, in partnership with Greater Cleveland Congregations, has found that the strategy known as relational organizing has succeeded in getting infrequent or new voters in Cleveland to commit to voting during the last two election cycles.

This technique proved effective even though research indicates “get out the vote” strategies may actually worsen the gap between frequent and infrequent voters. But relational organizing alone cannot overcome all the structural barriers to voting that exist in states like Ohio. When combined with integrated voter engagement (IVE) technology and strong relationships with local election administrators, it can be scaled up to increase turnout nationwide.

Building Relationships, Building Power

As part of our Science for a Healthy Democracy Campaign, the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) partners with Greater Cleveland Congregations (GCC), a nonpartisan organization of faith communities and partner organizations working to achieve social justice in Cuyahoga County, Ohio. GCC seeks to build power by encouraging more people to vote, which it does through a relational organizing program started in 2021.

Relational organizing involves semi-structured, one-on-one conversations with community members that strengthen interpersonal relationships, which in turn increases both individual political engagement and the strength of community voices on local, state, and national issues.

UCS has been providing GCC with support as it expands its relational organizing capacity with an integrated voter engagement (IVE) system. Through data-driven voter outreach, IVE programs have been shown to improve voter turnout in historically marginalized or underserved communities, building power that can yield benefits despite the structural barriers that result in inequities. IVE plays an especially important role for young people of color, creating an opportunity for leadership development, community organizing, and policy advocacy.

This report highlights the results of GCC's organizing efforts over the last two election cycles, and what it means for potential voter turnout in 2024. Our goal in working with GCC is to strengthen its relational organizing capacity and scale, while identifying how technology can improve outreach and voter turnout nationwide.

Organizing produced positive results

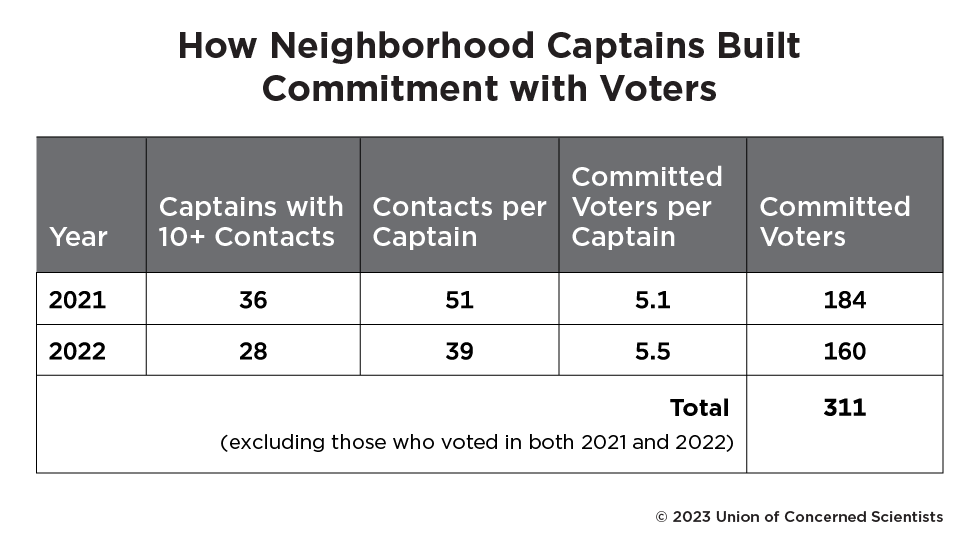

In 2022, GCC recruited and trained approximately 40 neighborhood captains to reach out to nearly 1,000 people who were registered but infrequent or new voters in Cleveland. The program was part of an ongoing local effort that began during the 2021 mayoral election. So far, neighborhood captains have successfully mobilized 311 voters across two election cycles (Table 1).

On average, contact success—defined as getting the persons contacted to commit to voting—for each active neighborhood captain across elections was between 40 and 50 voter households. The 2022 turnout rate among those who were contacted and committed to voting was 56 percent, compared with an overall turnout rate of 30 percent for the city of Cleveland. Each captain has been able to count on five to six voters on average to turn out on or before Election Day. While this may not sound like a lot, scaling up this program has the capacity to transform the electorate and strengthen the voice of marginalized communities, as we show below.

Being a neighborhood captain is participating in the battle to preserve the right for my neighbors to exercise their right to vote.

GCC focused its mobilization efforts in Cleveland's Wards 1, 2, 5, and 6, as well as select neighborhoods in Cleveland Heights and Warrensville Heights. Voter turnout varies greatly across these communities, due in part to differences in people's economic status, education, and health. But barriers to voting such as Ohio's early registration deadline, punitive voter registration drive laws, and restrictions on early voting and vote-by-mail also disproportionately impact already marginalized people.

Organizing reduced turnout inequalities

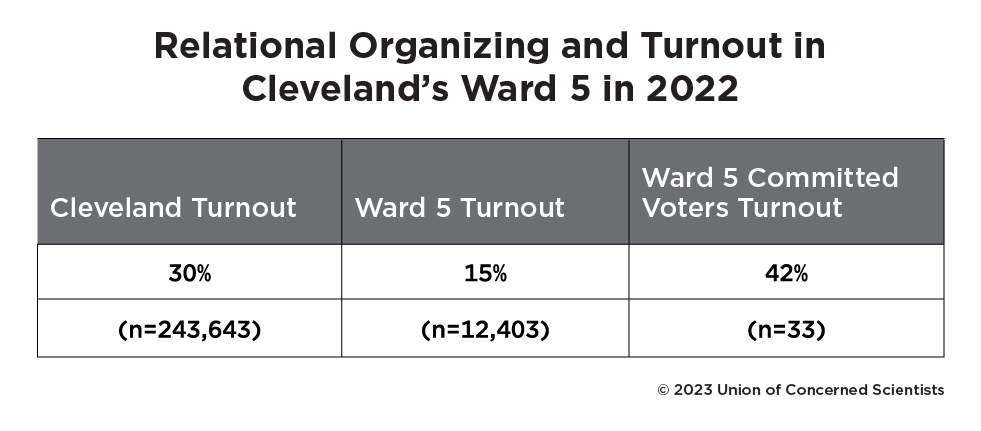

In Ward 5, traditionally Cleveland's lowest-turnout community, relational organizing showed a positive impact. In the November 2022 election, overall turnout in Ward 5 was just 15 percent—half that of the entire city. But among those who committed to voting through the neighborhood captains' efforts, turnout was 42 percent. Perhaps more importantly, the impact of relational organizing is higher in lower-turnout communities.

For example, in Cleveland Heights (Ward 4), overall turnout was 49 percent, and among committed voters reached 65 percent. While we observed higher turnout by committed voters across all socioeconomic levels, it is important to note that the effect was even stronger in Cleveland's Ward 5 (Table 2). Previous research has demonstrated that some common forms of "get out the vote" (GOTV) efforts actually worsen the participation gap between low- and high-propensity voters.

Organizing increased youth turnout

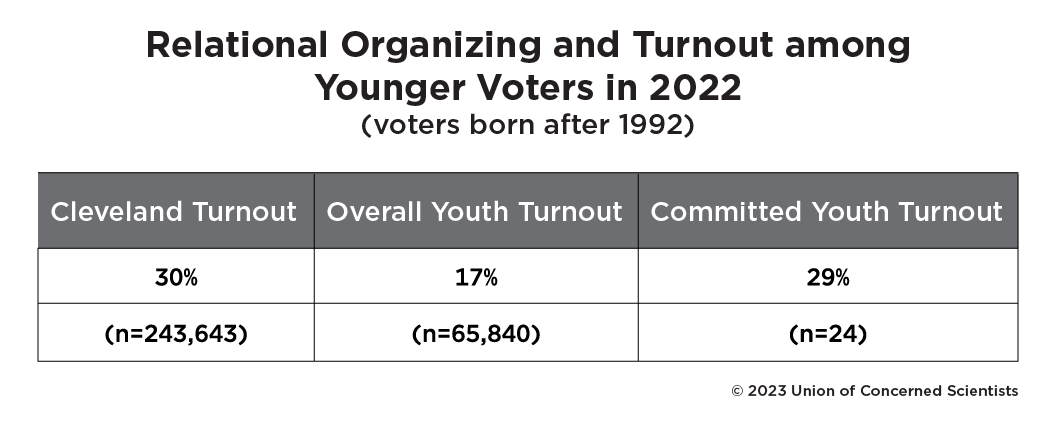

Similarly, we found that younger voters were more responsive than older voters when asked to commit to voting. The youngest voting cohort in the Cuyahoga County voter file—born after 1992—voted at an overall rate of about 17 percent, but those who committed to voting through relational organizing were nearly twice as likely to vote, close to the average turnout rate for Cleveland in 2022 (Table 3).

Challenges and areas for improvement

While these results are impressive, they are not conclusive, and it is important to note that the increased turnout among committed voters we observed is not just a function of relational organizing. Both self-selection bias (people who are more likely to vote are more likely to commit to voting) and treatment bias (people who are more likely to vote are more responsive to voter mobilization tactics) require the use of statistical controls in order to better estimate the impact of relational organizing.

After controlling for known predictors of turnout (previous voting history, age, ward-level turnout, inactive registration status), the impact of committing to vote remained statistically significant. Although these models show that factors including previous voting history, age, and social conditions that tend to dampen community turnout have a larger impact on the probability of voting, getting a commitment to vote still increased the odds of voting by about 75 percent, after controlling for those factors. Experimental treatments also suggest more modest organizing effects, and the small sample sizes that come from local programs make estimating general effects more difficult. Nevertheless, our analysis adds to the growing body of research showing the positive impact of community organizing efforts on political participation.

Our analysis also identified specific points in the chain of responsiveness where relational organizing efforts can be improved. First, the quality of contact data is crucial. Fewer than one-third (29 percent) of the voter lists yielded contacts with eligible voters and, as one precinct captain noted, "There were frustrations when we had bad addresses and phone numbers." One of the primary goals of IVE systems is to make it easier for election officials and precinct captains to share and update current voter data to improve efficiency and the accuracy of records.

Improved recruitment and training strategies will also increase the effectiveness of organizing. While the average voters-to-captain ratio was between five and six to one, there was considerable variation between precinct captains. Some were unsuccessful at getting people to commit to voting, while a single captain made nearly 200 contacts in low-turnout precincts in 2021, resulting in more than 40 committed voters.

Improved training and data will improve both the list-to-contact conversion and the contact-to-committed-voter conversion. Currently, each active captain yields about 10 commitments on average, for an overall contact-to-committed rate of about 16 percent. However, one in four captains converted 25 percent or more of their contacts, so we are confident that overall performance can be improved.

Finally, converting voter commitment into actual voter participation remains a challenge. While the evidence suggests that improved training will improve performance, the impact of structural barriers between voter intent and voter action is pronounced. Even here, though, relational organizing can have positive long-term effects. By listening to and lifting up voices in marginalized communities, and providing greater efficiency and effectiveness in building community leadership, structural voting barriers can be broken down and more inclusive, voter-friendly electoral laws can be implemented.

That includes fighting back against current legislative efforts in Ohio to weaken majority rule and silence the voices of voters. This August, the appropriately titled initiative "State Issue 1" is the number-one issue on the minds of voting rights and community leaders throughout the state. The measure would repeal the standard majority-rule requirement for passage of statewide initiatives, replacing it with a 60 percent supermajority threshold.

Ohio's legislative majority, already among the United States' most insulated political bodies thanks to restrictive election laws and partisan gerrymandering, is now trying to essentially impose minority rule by allowing 40 percent of voters to stop legislation that could address inequality in the state.

The need for effective organizing in Ohio—and other states—has never been greater.

Eight Steps to Strengthening Democracy through Relational Organizing

-

Accessing accurate data on eligible voters

-

Recruiting precinct captains

-

Training precinct captains

-

Converting voter lists into contacts

-

Listening to, recording, and lifting up community concerns

-

Converting contacts into committed voters

-

Documenting, analyzing, and publishing post-election information

-

Converting community engagement into more inclusive election laws

How scaling up organizing can transform an electorate

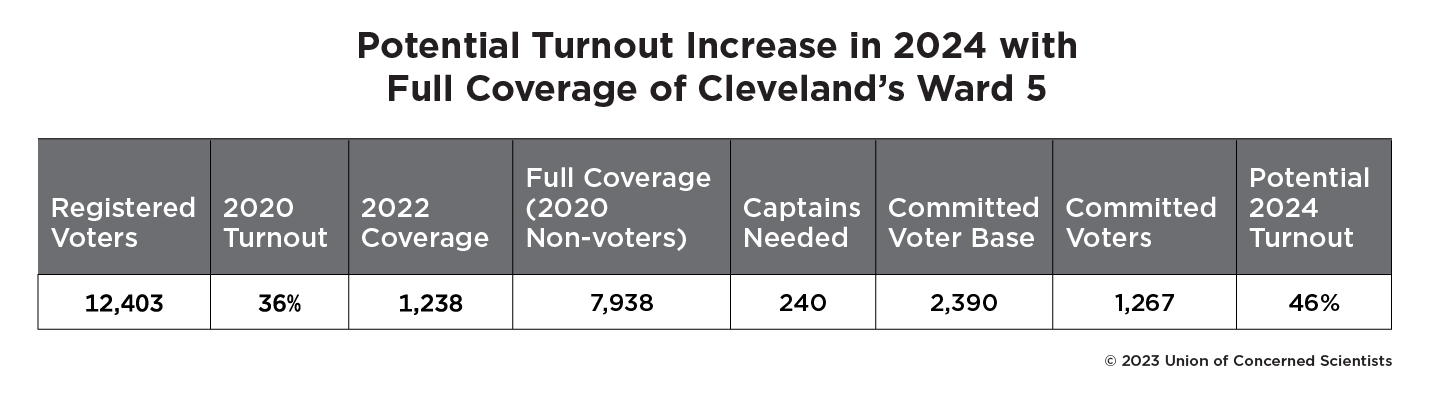

The data generated from this project allow us to forecast the effects on voter turnout if we could scale up GCC's relational organizing. We turn again to Cleveland's Ward 5 to demonstrate this potential. In the last presidential election (2020), just over a third (36 percent) of eligible Ward 5 voters participated. In 2022, the lists used by precinct captains only included about one-tenth (1,238) of the ward's 12,403 eligible voters.

In my opinion, the door knocking is most effective, so whatever we can do to increase the number of people who open doors will give us more successes.

We estimate it would require approximately 240 precinct captains to canvass all eligible Ward 5 voters who did not vote in 2020. With that much capacity, and using the same average conversion rates and adjusted 2020 turnout rates, we estimate that voter turnout in 2024 could be increased by 10 points over the last presidential election, or 46 percent, which is comparable to average turnout rates across the city (Table 4). Such a change would be truly transformative in reflecting the greater diversity and needs of the currently non-voting public.

As we learn more from contacts and conversations with different types of potential voters, we can use that information to improve objectives, tactics, and tools to better incorporate the needs of communities—and community members—into organizing efforts.

Between now and 2024

Relational organizing alone will not overcome persistent inequalities in voter turnout. Cultivating a voting habit and civic engagement can have long-term payoffs, but the voting inequalities observed over recent years point to structural deterrents that need to be addressed at the institutional level. We need technology such as IVE that improves the quality of election-related data, combined with strong relationships with local election administrators.

In Ohio, the Cuyahoga County Board of Elections has been an active ally of GCC on matters of data transparency. But the Ohio state legislature, one of the most gerrymandered in the country, has used election laws to further entrench its power.

Working together with community organizations like GCC, local election administrators, and other leaders, we can build out the technologies that will reinforce elections as opportunities to exercise collective action, improve registration and voter turnout, reduce participatory and representative inequalities, and contribute to leadership development.

The real road of compassion—that is, giving, helping, assistance, and community service—is a road that can be set and declared as your life’s purpose as a neighborhood captain.